Page views : 1313

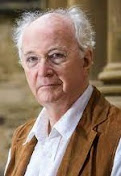

Dervla, who as a writer of over 25 travel books, written over half a century, had inspired and informed millions of readers throughout the world, has died at the age of ninety. She was born in Lismore, a historic town in County Waterford, in the province of Munster, Ireland, in the late autumn of 1931, the daughter of Dubliners, Kathleen and Fergus Murphy. When the doctor broke the news to Fergus who was at work as the County Librarian in the County Library in Waterford, he said : "Well now. I don't know if I should congratulate you or not. It's a daughter you have. Came at a quarter to twelve. Strong child".

The Ireland she was born into was a newly independent country, after Irish republican forces had fought and gained independence from the British just ten years before she was born and effectively became a republic with an elected non-executive president, when she was seven years old. In his youth, as a member of the Irish Republican Army, he was caught burying a weapon in his garden and sentenced to three years in Wormwood Scrubs Prison in London in 1918.(link)

.png)

.png) When Dervla was six months old, her mother, at the age of twenty four, was crippled with deadly painful, rheumatoid arthritis. She recalled : "Mother had rheumatoid arthritis. I never saw her walking or standing. All my memories of her are in a bath chair". Here, in this garden scene, her father reads a book and her mother, in her bath chair, has Dervla on sitting on her lap.

When Dervla was six months old, her mother, at the age of twenty four, was crippled with deadly painful, rheumatoid arthritis. She recalled : "Mother had rheumatoid arthritis. I never saw her walking or standing. All my memories of her are in a bath chair". Here, in this garden scene, her father reads a book and her mother, in her bath chair, has Dervla on sitting on her lap.

.png)

Obviously, as a child she was denied all the pleasure of running and playing in the garden with her mother and as, by the decision of her parents, an only child, she was also without the company of siblings. Many years later she would write : 'Only when I was a mother myself did I appreciate how my own mother must have felt when she found herself unable to pick me up, and brush my hair, and tuck me up in bed'. She recalled : "When I was very small I used to spend hours standing in a corner with my back to the world, talking aloud to myself. And I had an aunt who was a child psychiatrist and she became very concerned about this and told my parents that I needed a course of therapy to 'normalise' me and so on".

.jpg)

.jpg) Dervla was to live in the small town of Lismore for the whole of her life and said that it was : "Set in very beautiful countryside and I grew up within easy walking or cycling distance of wide ancient woodlands with mighty trees to climb, a deep river to swim in and low mountains to climb".

Dervla was to live in the small town of Lismore for the whole of her life and said that it was : "Set in very beautiful countryside and I grew up within easy walking or cycling distance of wide ancient woodlands with mighty trees to climb, a deep river to swim in and low mountains to climb".

Books became very much part of her life from a young age. Her mother encouraged her to read them with her and, as a child, she enjoyed writing and gave her parents short stories or essays as Christmas and birthday presents. She remembered writing : "Stories about a family of teddy bears that I'd invented and they lived in a really big tree. It was divided into little villages. Those went on for quite a few years". She said : "My Mother was my mentor when I was trying to write as quiet a small child. She would criticise everything I wrote in a constructive sense, pointing out what was wrong and how this could be improved". As for Fergus, her father, she said that in her early years : "I had some modest success as a writer because my father himself always wanted to be a writer". She was referring to articles she had published, while Fergus, over a number of years, had endured the disappointment of receiving only rejection slips for the novels he had submitted to publishers.

Dervla's life changed in 1941 and, she recalled : "It was knowing very definitely, there was something I knew I wanted to do in the course of my life and that was cycle to India. I was ten and I'd just been given a second-hand bike for my tenth birthday and an atlas by my grandfather and I discovered, not being very good at geography, you could, apart from getting across to Turkey, you could cycle all the way from Europe to India. And one day, early in December, just about a week after I got these two gifts, I was cycling up a hill and remember looking down and thinking : 'If I went on doing this for long enough I'd actually get to India just turning the pedals’ “.

.png)

.jpg) "One of the reasons I enjoyed going off to boarding school, after that first terrible week of homesickness, I suddenly felt liberated. I was just one of how many hundreds. It was nobody commenting whether my vest was dried ? My shoes were leaking ? or whatever".(link) At the age of twelve, she is seen here on the day of her confirmation into the Catholic Church in 1953.

"One of the reasons I enjoyed going off to boarding school, after that first terrible week of homesickness, I suddenly felt liberated. I was just one of how many hundreds. It was nobody commenting whether my vest was dried ? My shoes were leaking ? or whatever".(link) At the age of twelve, she is seen here on the day of her confirmation into the Catholic Church in 1953.

She also recalled : "I knew when I was young that I'd never marry and the sense that I would be a writer and although there was no talent showing at this stage, that I might possibly achieve the writing ambition, but this was knowledge in another sort of plain. And just knew I wouldn't marry".

Her freedom from home, at school, would prove to be short lived : "I had to leave boarding school When I was thirteen, well, nearly fourteen, and come home to look after my mother because her condition was gradually worsening and this was during the Second World War and we couldn't get any servants, anybody to look after her. But I was delighted to leave school because I knew I'd never pass an exam. I wasn't interested in passing exams. I knew what I wanted to do and exams seemed completely irrelevant to that. So that seemed to be a great release for a few years, but things got more and more difficult. My mother's health became worse and worse".

In this situation, her rides alone on her bicycle became more and more important and this was something recognised by her mother and Dervla recalled that when she was wondering whether she could cycle down the southern Irish coast her mother would say : "Well of course you can if you want to" and she encouraged her : "To feel if you really want to do something you can do it".

In fact, it was when she was seventeen, that she made her first journey out of Ireland, by ferry, to mainland Britain and Pembrokeshire in North Wales and said : "The Second World War restricted my movements until 1948 when a cattle-boat took me and my bicycle from Waterford to Fishguard. There I began a month of pedaling around Wales and England, pausing for a week in London where at that time even a teenager on a shoe-string could afford concerts and opera". The journey also led to her writing a series of articles published in Dublin based journal 'Hibernia' and later she had work published in the 'Irish Independent' newspaper.

Occasionally, her father took over her nursing and domestic duties for a day, but usually she was never off duty for more than four hours at a stretch, between 6 and 10 pm. She recalled that the day's off : "Left me free to enjoy a serious cycle of sixty or seventy miles". Dervla took her cycling seriously and clearly pushed herself hard. She taught herself to endure pain by devising endurance tests which involved putting her feet in very hot water and : "Tying a string around your finger and pulling it tighter and tighter and learning, in a funny kind of way, how to repair - that kind of thing".

When Dervla was in her twenties, in the 1950s, the situation at home became increasingly difficult. Her mothers kidneys began to fail and she became totally dependent on Dervla and insisted she shared a bedroom with her. She recalled : "She needed her position to be shifted frequently to relieve the pain, which meant that for quiet a number of years I never got an unbroken night's sleep and that got me down quite badly, as I think it would of any young person. When my father died eighteen months before my mother died I must have had a complete breakdown, because I can record very little of that 18 month period. I went on the whisky in a serious way, chain smoked, ate very little, had broken night's sleep and was generally a wreck". (link)

Eventually it was arranged that she would have three hours a day on week days, free which helped and she wrote in her autobiography : 'It needed only this break in the automaton rhythm of the past months to release the cataract of despair. I was nearly thirty and had achieved - it then seemed nothing-nothing. As a daughter I was a failure, as a woman I was ageing, as a writer I was atrophied, as a traveler I had only glimpsed possibilities'. Dervla confessed to Sue Lawley on the BBC Radio programme, 'Desert Island Discs' in 1993 that she did contemplate putting an end to her mother's life and said : "If it had gone on from for another three four five years I might well have done it".(link)

When her mother died in at the age of fifty-four in 1961, Dervla described it was both a "release" and also experienced a "tremendous sense of guilt". Nevertheless now, alone in the house, she found some peace and wrote : 'Love leaves calm. Even when the circumstances have given it the semblance of hate, this is so. In the tangled relationships between my parents and myself, love was often abused, denied, misdirected, thwarted, exploited and outwardly debased. But it existed, and it left calm".

She now saw that the previous years had not been wasted and wrote : 'At thirty, I could ignore neither my own flaws not the endless variety of causes that can lie behind the flaws of others. The school was hard, but the knowledge was priceless' and ' Had I left home at eighteen and made a successful career for myself, I would probably made a successful career for myself, I would have probably gone through life as an intolerant, unsympathetic bitch - a role for which I had, as a youngster, all the necessary qualifications'.

.png)

She said that when she went into a cycle shop to have the gears removed because she was going to India and didn't think they were suitable for Asian roads :

'The mechanic looked at me very strangely indeed'.

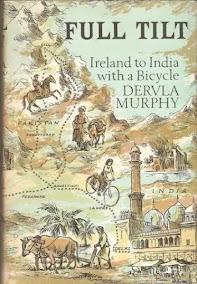

She said she planned what proved to be : 'A happy-go-lucky private voyage to enjoy some of the world in the way that best suited my temperament. And, if publishing trade winds were blowing my way, to provide material for a book'. She now crossed the English Channel and began the start of her epic journey in France and said : "In the winter of 1962-63 I remember cycling to Rouen with a very large icicle hanging off the end of my nose". However, she wrote : 'None of the privations, hazards or unforeseen difficulties bothered me. To be able to gratify my wanderlust, after so many years of frustration, was all that mattered'.

Before leaving with Roz Dervla had taken the precaution of posting ahead several spare tyres to embassies en route. Nearly fifty years later, in 2011, when she was asked by a member of the audience of a programme televised in the USA : "I was curious if you were joking, when you said you didn't know how to fix a puncture" : "No, I was deadly serious" and when the questioner continued : "And flats ?" Dervla replied : "Of course". And when asked : "And how did you fix them ?" She replied : "I just sat down and waited for a man to come along". (link)

What followed was her six-month journey through Europe, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and over the Himalayas into Pakistan and India. The result of her journey was her first book, 'Full Tilt: Ireland to India with a Bicycle' which was published in 1965 and established her as an exceptional new voice among travel writers. In Yugoslavia, she began to write a journal instead of mailing letters and this had formed the basis of the book..jpg) Within the first month of her journey, in Bulgaria, when stranded in a snowdrift, she was confronted by a pack of wolves as they tore at her clothes and saw them off with shots from the .25 pistol she carried with her.(link) Before she left home, she had been given an introduction to its use by the Waterford Garda taken and practiced firing in the mountains around Lismore. She used it again in Turkey, when a “scantily clad” Kurdish intruder bent over her, in the moonlight, in the hostel room where she was staying and she fired a warning shot into the ceiling which sent him running.(link)

Within the first month of her journey, in Bulgaria, when stranded in a snowdrift, she was confronted by a pack of wolves as they tore at her clothes and saw them off with shots from the .25 pistol she carried with her.(link) Before she left home, she had been given an introduction to its use by the Waterford Garda taken and practiced firing in the mountains around Lismore. She used it again in Turkey, when a “scantily clad” Kurdish intruder bent over her, in the moonlight, in the hostel room where she was staying and she fired a warning shot into the ceiling which sent him running.(link)

Once, on a blistering hot day on a desolate road in Iran, an American engineer stopped in his Jeep to offer Dervla a ride and said : “This track isn’t fit for a camel”. To which she replied : “When you’re on a bicycle, instead of in a Jeep, it doesn’t feel like a frying pan.” To which he replied : “You are a goddam nut case!” (link) She reflected, when recounting the incident : “I regard this sort of life with just Roz and me and the sky and the earth as sheer bliss”. It was in Iran she used her gun again to frighten off a group of thieves, and "used unprintable tactics" (a knee in the balls), to escape from an attempted rapist at a police station. (link)

In the mullah-dominated country of the Great Salt Desert she found herself stoned by youths one day, but followed by adoring schoolboys clutching copies of 'Jane Eyre' the next.

Dervla always denied that she was brave : "Because isn't true. I think 'fearless' is true. But that is a totally different thing. If you don't feel fear, you don't have to be brave. You're brave when you're overcoming fear". She wasn't afraid when travelling, although she admitted being "creeped" by certain landscapes.(link)

She received her worst injury of the journey on a bus in Afghanistan, when a rifle butt hit her and fractured three ribs during a fracas on a bus between a group of Afghan men. It caused her much pain for several weeks, but only delayed her for a short while. She wrote appreciatively about the landscape and people of Afghanistan, calling herself "Afghanatical" and claiming that 'the Afghan' : "Is a man after my own heart".

.jpg)

She said that : Ancient Herat was : 'A city of absolute enchantment', compared the bounteous Ghorband Valley to the Garden of Eden and was moved by the : 'Incredible, unforgettable beauty' of the mountains of the Hindu Kush. 'At times during these past weeks', she wrote in 'Full Tilt' : 'I felt so whole and so at peace that I was tempted seriously to consider settling in the Hindu Kush. Nothing is false there, for humans and animals and earth, intimately interdependent, partake together in the rhythmic cycle of nature. To lose one’s petty, sophisticated complexities in that world would be heaven — but impossible, because of the fundamental falsity involved in attempting to abandon our own unhappy heritage.' It was in Afghanistan that she sold the pistol.

Having passed into Pakistan, she exercised her resourcefulness on the freezing Babusar Pass in Pakistan, tied herself to a cow to get across a raging watercourse or 'nullah'. .jpg) In Pakistan, she visited Swat where she was a guest of the last crown prince, Miangul Aurangzeb, and then moved on to mountain area of Gilgit. The final leg of her trip took her through the Punjab region and over the border to India and towards Delhi and when she arrived in the city on July 18, 1963, she estimated she had covered about 3,000 miles, cycling an average of 70 to 80 miles a day.

In Pakistan, she visited Swat where she was a guest of the last crown prince, Miangul Aurangzeb, and then moved on to mountain area of Gilgit. The final leg of her trip took her through the Punjab region and over the border to India and towards Delhi and when she arrived in the city on July 18, 1963, she estimated she had covered about 3,000 miles, cycling an average of 70 to 80 miles a day.

After arriving in Delhi, she worked as a volunteer helping Tibetan refugees under the auspices of 'Save the Children' and spent five months in a refugee camp in Dharamsala run by Tsering Dolma, sister of the 14th Dalai Lama. Here, she worked with a team of western and Indian staff to feed and bathe the children, giving them medicine and battling against the rampant spread of scabies. She later said that of all the people she had met on her travels, the staff there were those who had impressed her the most. (link)

She then cycled through the Kullu Valley, spending Christmas in Malana. Her journals from this period were published in her second book, 'Tibetan Foothold'. She said her biggest regret was that she had not ventured into Tibet itself.

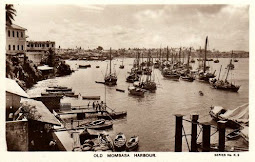

Dervla had now fallen into the system of using the proceeds of her last book to finance her next trip, which in 1966 was her first to Africa. She travelled to Ethiopia and  walked with a pack mule she named 'Jock', after Jock Murray, her publisher, from Asmara to Addis Ababa and was confronted by Kalashnikov-carrying soldiers on the way.

walked with a pack mule she named 'Jock', after Jock Murray, her publisher, from Asmara to Addis Ababa and was confronted by Kalashnikov-carrying soldiers on the way. She later described this three month solo trek with Jock through the Simien Mountains at a time when there were no motor roads or towns along my route as her 'proudest achievement'.jpg) and described it in her fourth book, 'In Ethiopia with a Mule'. Yet at times it was fraught with danger, witness the fact that she was robbed three times, once by armed bandits who nearly decided to kill her. She conceded : “That was nasty, and I knew it was very much in the balance. I was lucky then. Extremely lucky”.

and described it in her fourth book, 'In Ethiopia with a Mule'. Yet at times it was fraught with danger, witness the fact that she was robbed three times, once by armed bandits who nearly decided to kill her. She conceded : “That was nasty, and I knew it was very much in the balance. I was lucky then. Extremely lucky”.

In 1967, her pregnancy by design and birth of her daughter Rachel, was the result of an affair with Terence de Vere White who was married, almost twenty years her senior and the literary editor of the 'Irish Times'. She recalled : "He said, "I wonder what a child of ours would be like ?" and I said : "Let's go for it and find out". I was 36 and I wasn't sure it was going to work. I made the rule that I would be totally responsible for the baby".

In 2011, when she was eighty years old, she said : "I never felt my travels were getting in the way of my relationships, because the people who had relationships with me recognised at the beginning that I'd be here one minute and gone the next".(link). She didn't reveal Terence's identity until his death in 1994.

For the first few years Dervla stayed at home with Rachel and contented herself by writing book reviews for the 'Irish Times'. Her decision to bring up her child on her own was considered by some a a brave choice in 1960s Ireland, but she said she felt safe from criticism because she was in her thirties and was financially and professionally secure. In addition, she recalled how neighbours brought : “All sorts of knitted items” for newborn Rachel and what really scandalised the locals, she said was the fact that she took her baby out naked in her pram to get some sunlight.

.jpg)

Soon after Rachel turned five, Dervla flew with her to Bombay and travelled to Goa and Coorg and the resultant book : 'On a Shoestring to Coorg' was published in 1976. (link) They spent six months in the south of India and then the winter travelling through the remote, icy passes of Baltistan, beneath K2 high in the Karakoram Range.

Dervla recalled : "In Baltistan when I was there when I was with my daughter in the middle of winter, neither of us took our clothes off, literally for three months. Not once. I mean the temperature went to minus 40 at night there, so at bed time you didn't like taking your clothes off .The Tibetans say the natural oils form a 'carapace'. You're sealed in as it were". She added : "I regret to say the thaw had just come and when the that comes, little things begin to breed. So we had body lice when we took them off". In the resultant : 'Where the Indus is Young' she was able to write : 'The grandeur, weirdness, variety and ferocity of this region cannot be exaggerated'. .jpg)

Dervla had bought a retired polo called 'Hallam', on which Rachel rode, along with bundles of camping gear and their supplies. For three months they travelled along the perilous Indus Gorge and into nearby valleys and together they made arduous journeys from village to village, surviving on the occasional luxury of boiled eggs, but more often on handfuls of dried apricots and slept on the floors of flea-infested guesthouses. Dervla found that, to some extent, Rachel was an asset and said that children : "Rapidly demolish barriers of shyness or apprehension often raised when foreigners unexpectedly approach a remote village”.

Dervla said : “People considered it insanity for us to set out with only basic supplies to a part of the country that had no roads, no hospitals, no services. But that was why we were there in the first place”. They both remained unflagging in their sympathetic response to the perilous beauty and impoverished people of the Andes they met on the way. Further journeys with Rachel involved 'Muddling through in Madagascar' in the early 1990s and Cuba with Rachel and her three granddaughters, when she was seventy-four in 2005.(link) When asked in one interview why she continued to travel, Dervla said : “I was born that way. I need to get away from the artificial life of the West. When I set out on a journey, my spirits rise. I’m never lonely or frightened”.

Dervla visited had Rwanda not long after the 1994 genocide and said : “Rwanda forces one to confront the evil inherent in us all, as human beings, however humane and compassionate we may seem as untested individuals". However, on another occasion her conclusion, based on her travels, was that : “Something I have learned is that most people are helpful and trustworthy. That people are generally good ".(link)With perfect understatement she said, looking back on her life : “Clearly there have been discomforts and extremes of temperature – though not a great deal. But I am not going out to 'overcome something', like an explorer or serious mountaineer. I am travelling to enjoy myself”.

When she received the 'Edward Stanford Award' for 'Outstanding Travel Writing' in 2021, Michael Palin, documentary television traveler, told her in a video tribute : “What you have is this mixture of open honesty combined with fearlessness. You’ll ask anybody anything and they’ll open up and talk to you, and it’s your ability to give yourself to the people you’re talking to that makes for great revelations”. (link) Apparently, when he was visiting her, some five years before, for a television documentary, 'Who Is Dervla Murphy?' (link) , in which he said : “You can’t process Dervla – she just is what she is”, when she asked him to join her daily skinny dip in the River Blackwater, he declined.(link)

When she received the 'Edward Stanford Award' for 'Outstanding Travel Writing' in 2021, Michael Palin, documentary television traveler, told her in a video tribute : “What you have is this mixture of open honesty combined with fearlessness. You’ll ask anybody anything and they’ll open up and talk to you, and it’s your ability to give yourself to the people you’re talking to that makes for great revelations”. (link) Apparently, when he was visiting her, some five years before, for a television documentary, 'Who Is Dervla Murphy?' (link) , in which he said : “You can’t process Dervla – she just is what she is”, when she asked him to join her daily skinny dip in the River Blackwater, he declined.(link)

.jpg)

With her passing, the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, said : "Her contribution to writing, and to travel writing in particular, had a unique commitment to the value of human experience in all its diversity".(link)

Back in 1965, after a meeting at the publishers John Murray in London, where she was told it had accepted he book for print and met her editor Jane Boulanger.(link) She left and walked through St James's Park. She wrote that she reflected on the disappointment of her father's rejected novels and wrote : 'It was chance that in my lifetime - perhaps because of my mother's contribution to the genetic pool - all the strivings of generations of scribbling Murphys were to push their way above ground into print. And so on that sunny June day by the duck ponds, the acceptance of my first book seemed less a personal triumph than the fulfilment of an obligation to my parents'.

* * * * * * * * *

In grateful acknowledgement to Derval's autobiography, 'Wheels within Wheels'

* * * * * * * * *

And that other great traveler, Geoff Crowther, who predeceased Dervla by one year :

.jpg) James Graham, the writer of the critically acclaimed BBC TV series, 'Sherwood', who did a drama degree at Hull University saw the move as part of a trend, with arts and creative subjects slowly disappearing not just from higher education but from primary and secondary schools as well. He said : “It’s just deeply depressing that one of the great British success stories of the last few years – the arts and entertainment industry – is going to be systemically weakened and diminished because it is being eradicated from education in the UK”.

James Graham, the writer of the critically acclaimed BBC TV series, 'Sherwood', who did a drama degree at Hull University saw the move as part of a trend, with arts and creative subjects slowly disappearing not just from higher education but from primary and secondary schools as well. He said : “It’s just deeply depressing that one of the great British success stories of the last few years – the arts and entertainment industry – is going to be systemically weakened and diminished because it is being eradicated from education in the UK”..jpg) Sarah Hall, an author and Professor of Practice at the University of Cumbria, reflected on the University’s decision to stop teaching the standalone English Literature Degree and incorporate it instead into a broad-based English Degree. She said : “It’s awful, absolutely awful. I wish it wasn’t happening.”

Sarah Hall, an author and Professor of Practice at the University of Cumbria, reflected on the University’s decision to stop teaching the standalone English Literature Degree and incorporate it instead into a broad-based English Degree. She said : “It’s awful, absolutely awful. I wish it wasn’t happening.” .jpg) Michelle Donelan, the Minister for Higher and Further Education and a History and Politics graduate from the University of York, put forward, what this Government would call a "robust "defence" of its position when she said that it recognised that all subjects, including the arts and humanities, can lead to positive student outcomes but : “Courses that do not lead students on to work or further study fail both the students who pour their time and effort in, and the taxpayer, who picks up a substantial portion of the cost”. I have the feeling that Jo and James and Sarah and Sarah would disagree with her and side with Phillip and sadly :

Michelle Donelan, the Minister for Higher and Further Education and a History and Politics graduate from the University of York, put forward, what this Government would call a "robust "defence" of its position when she said that it recognised that all subjects, including the arts and humanities, can lead to positive student outcomes but : “Courses that do not lead students on to work or further study fail both the students who pour their time and effort in, and the taxpayer, who picks up a substantial portion of the cost”. I have the feeling that Jo and James and Sarah and Sarah would disagree with her and side with Phillip and sadly :

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.png)