He was born in Birmingham in Kings Norton, a southern suburb of Birmingham in 1919, the son of Ida and Leslie, who had been the Chief Metallurgist to the Air Ministry during the First World War and remained so until Martin was five, when he became the assistant to Horace Clarke the the MD of a subsidiary of the Vickers, the aircraft manufacturers. The most traumatic event in his childhood took place when, after contracting the measles, his hearing was severely impaired. For his education from the age of 11, was packed off to the boys independent boarding school, Ellesmere College in Shropshire where he recalled : "Few people enjoyed school in those days and my deafness didn't help. They started off putting me at the front of the class and when I still struggled they put me at the back."

When it came to Martin's artistic development he said : "The idea took root when I was at school really. At about the age of 13 I discovered I could get some cheap popularity with my ability to caricature the school masters." Two years later, in 1934 school was over for Martin : "I left school at the age of 15 and there hadn't been any discussion of my future career. But they did give me all the drawing prizes, some very handsome books and I think my family were delighted that I could do something well, despite my deafness."

When it came to Martin's artistic development he said : "The idea took root when I was at school really. At about the age of 13 I discovered I could get some cheap popularity with my ability to caricature the school masters." Two years later, in 1934 school was over for Martin : "I left school at the age of 15 and there hadn't been any discussion of my future career. But they did give me all the drawing prizes, some very handsome books and I think my family were delighted that I could do something well, despite my deafness."Martin, 'becapped' and in school uniform stands on the right.

His precocious artistic talent took him first to Birmingham School of Art, where he thought he "learnt most from the other students" and then to the Slade School of Art in London, where he was a student when he exhibited at the Royal Academy at the age of 20 in 1939. On the outbreak the Second World War in the same year Martin was 'called up' for active service but his profound deafness, confirmed at his medical, precluded service in the Armed Forces,

Instead, he joined Vickers Aircraft at Weybridge, Surrey where his talent was initially used to illustrate operating manuals for aircraft such as the Wellington bomber. It wasn't long before his father's connection with an old pre-First World War university friend, Barnes Wallis, secured him a post on his team at Vickers. On joining he found Wallis "was friendly and aimed to make me an aircraft designer till he found out that my knowledge of mathematics was subnormal. So then he asked me to create diagrams of the effects, etc, of the bouncing bomb." The bomb in question had originated in 1942, when Wallis began experimenting with skipping marbles over water tanks in his garden, leading to his paper : 'Spherical Bomb — Surface Torpedo'. The idea was that a bomb could skip over the water surface, avoiding torpedo nets, and sink directly next to an enemy battleship or dam wall as a depth charge, with the surrounding water concentrating the force of the explosion on the target.

Instead, he joined Vickers Aircraft at Weybridge, Surrey where his talent was initially used to illustrate operating manuals for aircraft such as the Wellington bomber. It wasn't long before his father's connection with an old pre-First World War university friend, Barnes Wallis, secured him a post on his team at Vickers. On joining he found Wallis "was friendly and aimed to make me an aircraft designer till he found out that my knowledge of mathematics was subnormal. So then he asked me to create diagrams of the effects, etc, of the bouncing bomb." The bomb in question had originated in 1942, when Wallis began experimenting with skipping marbles over water tanks in his garden, leading to his paper : 'Spherical Bomb — Surface Torpedo'. The idea was that a bomb could skip over the water surface, avoiding torpedo nets, and sink directly next to an enemy battleship or dam wall as a depth charge, with the surrounding water concentrating the force of the explosion on the target.Wallis had been commissioned to produce the bombs for the RAF to destroy the dams in the industrial Ruhr area of Germany and it was Martin's job to create an artistic impression of how they would work as they shed layers as they skimmed off the heavily protected surfaces of Germany’s powerhouse dams. Martin later said : “I never felt under pressure from work, but everything we worked on was top secret. Occasionally the tea lady would take an interest in one of my drawings so we had to make up elaborate stories about what they were for.”

The successful raid on the dams in 1943 known to Martin as "Operation Chastise', was immortalised after the War in Paul Brickhill's book, 'The Dam Busters' and, of course, the 1955 film of the same name. Wallis himself placed credit with Guy Gibson and 617 Squadron : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=35qsu9HsYos&t=16m04s

It was during the War that, at the age of 24, Martin married fellow Slade student, Dorothy Self, who, as he recalled was "quite a prominent student at the Slade. We got married in 1943, although she had worked he way through three other fiancées by then."

With the War over, Martin now became a freelance commercial artist for various advertising agencies, national newspapers and publications such as 'Picture Post' and 'Punch'. At the same time his father's career in academia continued to flourish, he ad been made a 'Fellow in Industrial Metallurgy' and in 1946, when Martin was 27, became the Professor of Industrial Metallurgy at Birmingham University.

Martin's first work for children was for 'Girl' Magazine which had been launched by Hulton Press in 1951 as a sister paper to the 'Eagle.' He drew, filling in for Ray Bailey on 'Kitty Hawke and her All-Girl Air Crew' and illustrating 'Flick and the Vanishing New Girl' in the first Girl annual.

Martin's first work for children was for 'Girl' Magazine which had been launched by Hulton Press in 1951 as a sister paper to the 'Eagle.' He drew, filling in for Ray Bailey on 'Kitty Hawke and her All-Girl Air Crew' and illustrating 'Flick and the Vanishing New Girl' in the first Girl annual.In 1952, at the age of 33, he got a job illustrating at the 'Eagle' which was "meant to last for 12 weeks, but it ended up lasting for 11 years" ten of which involved drawing the French Foreign Legion strip, 'Luck of the Legion', written by Geoffrey Bond which he recalled as : "It was great fun doing these stories but I had to work very hard, turning out a whole edition every week" and "I used to show them to my son Nick when he was six but I think he was a bit young for them — he looked terrified."

The series followed the exploits of the French Foreign Legion in North Africa, then largely French-colonised or controlled and focused mainly on the chisel-jawed British hero Sergeant "Tough" Luck and his faithful companions, Belgian Corporal Trenet and Italian Legionnaire Bimberg who was the comic relief, short and fat and perpetually dishevelled, with a battered kepi. The strip was set in a vaguely pre - First World War period of colourful uniforms and unquestioned imperial values.

The series followed the exploits of the French Foreign Legion in North Africa, then largely French-colonised or controlled and focused mainly on the chisel-jawed British hero Sergeant "Tough" Luck and his faithful companions, Belgian Corporal Trenet and Italian Legionnaire Bimberg who was the comic relief, short and fat and perpetually dishevelled, with a battered kepi. The strip was set in a vaguely pre - First World War period of colourful uniforms and unquestioned imperial values.Martin was forced to use a deal of poetic licence : "For me the desert spelt Lawrence of Arabia and romance. So I liked the subject matter and I like the freedom I was given. Working from imagination pleased me most, but the lack of references caused me headaches too. Hulton Picture Library could find only four reference photos of the Foreign Legion. I watched an American film about the Legion and that was about it." This explains why Martin's illustrations usually took Luck and his companions and by implication, the Eagle's boy readers to isolated forts located in the Sahara where their adversaries were generally tribesmen whose dress was inexplicably Saudi Arabian rather than Algerian or Moroccan.

For the Eagle, Martin also illustrated the spy series 'Danger Unlimited', which was an attempt to update Eagle with a James Bond type story line and adaptations of Arthur Conan Doyle's 'The Lost World' and C. S. Forrester's 'Horatio Hornblower' stories and 'Arty and Crafty', written by Geoffrey Bond, for Eagle's junior companion paper, 'Swift'.

Martin recalled that in 1963 at the age of 44 : “After 10 years illustrating the Luck of the Legion strip for Eagle comic, the Eagle went bust so I was suddenly out of work” but once again his well-connected family came to the rescue : “My father met Douglas Keen at art classes in Stratford where they both lived and he mentioned me to Douglas.” Douglas was the new and radical editor of Ladybird Books who, with his socialist beliefs, believed in education for all children and set about transforming the company by investigating themes of both breadth and depth, finding writers and educationists and commissioning artists. Martin himself confessed that : "I really hadn't come across Ladybird books before then and I wasn't that inspired by the quality of illustration initially."

It wasn't plain sailing for Martin. His first drawing for Douglas was rejected before he submitted another, which was accepted and included in 'A First Book Of Saints.' Together with Harry Wingfield, Martin went on to illustrate the majority of the 'Ladybird Key Word Reading Scheme' , sometimes known as the 'Peter and Jane' books, which appeared between 1964 and '67 and were used to teach hundreds of thousands of British children to read and went on to sell over 80 million copies worldwide.

Each book took Martin about 3 months to complete. His preferred method was to work from photos and his wife Dorothy, who was herself a teacher at the Kingston School of Art was his model for the teacher in Book 6a and provided the script for a number of his illustrated fairy tales including 'Snow White and Dwarfs.'

Each book took Martin about 3 months to complete. His preferred method was to work from photos and his wife Dorothy, who was herself a teacher at the Kingston School of Art was his model for the teacher in Book 6a and provided the script for a number of his illustrated fairy tales including 'Snow White and Dwarfs.'  Martin said, with perfect self-effacement and his hallmark humour : “I just illustrated the script, set in everyday life around me – North London suburbia in my case. If the sky was always blue, it was probably because we waited for a fine day to take reference photos. After years of illustrating the French Foreign Legion going into battle, drawing children eating ice-cream took a little getting used to!”

Martin said, with perfect self-effacement and his hallmark humour : “I just illustrated the script, set in everyday life around me – North London suburbia in my case. If the sky was always blue, it was probably because we waited for a fine day to take reference photos. After years of illustrating the French Foreign Legion going into battle, drawing children eating ice-cream took a little getting used to!” His talent as an illustrator with his consistency, naturalistic style and attention to detail meant that he was a valued member of the Ladybird team and his work has been admired for its understanding of human character and his vivid delineation of so many expression of the emotions which was unparalleled in any other Ladybird artist.

Martin worked for Ladybird Books for over 20 years, illustrating nearly 100 titles. At the start he was paid £21 per picture which had risen to £60 for a single page and £120 for a double in 1975. He confessed that the work which gave him the greatest satisfaction was the double page spreads for the 'Hornblower Series' for the Eagle around 1962 and his illustration of 'Gulliver' stealing the Big-Endian fleet for Ladybird. It is surprising that he didn't mention his 'The Story of Metals' with its text provided by his 'Professor of Metallugy' father, Leslie, who had published his doubled volume, academic, 'History of Metals' in 1962.

Martin worked for Ladybird Books for over 20 years, illustrating nearly 100 titles. At the start he was paid £21 per picture which had risen to £60 for a single page and £120 for a double in 1975. He confessed that the work which gave him the greatest satisfaction was the double page spreads for the 'Hornblower Series' for the Eagle around 1962 and his illustration of 'Gulliver' stealing the Big-Endian fleet for Ladybird. It is surprising that he didn't mention his 'The Story of Metals' with its text provided by his 'Professor of Metallugy' father, Leslie, who had published his doubled volume, academic, 'History of Metals' in 1962.Martin left Ladybird in 1987 at the age of 68 and officially 'retired' with the exception of illustrating a new comic strip, 'Justin Tyme - ye Hapless Highwayman', written by Geoffrey Bond and later his son Jim, for the fanzine 'Eagle Times' from 1998 to 2004.

In 2012, at the age of 93 he featured in a BBC TV programme in the 'See Hear' series and recalled an incident at Ladybird where he got into trouble with an illustration about rock climbing where he "put the boy abseiling and it was completely wrong and if anybody had tried to do that he would have spun off and gone down and the mountain rescue people in Keswick complained about it and we had to rearrange the ropes and republish the book. That's the worst thing I ever did" :

In 2012, at the age of 93 he featured in a BBC TV programme in the 'See Hear' series and recalled an incident at Ladybird where he got into trouble with an illustration about rock climbing where he "put the boy abseiling and it was completely wrong and if anybody had tried to do that he would have spun off and gone down and the mountain rescue people in Keswick complained about it and we had to rearrange the ropes and republish the book. That's the worst thing I ever did" :http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00ykz6d

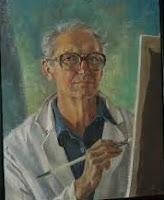

Martin once said :

"I sometimes look back a bit wistfully on my original intention to be to be a painter and wonder how it would have fared."