Yesterday, the 80 year old rocker, Rod Stewart, welcomed the 90 year old, Michael to the Pyramid Stage on what was the Glastonbury Music Festival's 55th Birthday and orchestrated the huge audience to sing 'Happy Birthday' to Michael.(link)

Rather than work on the family farm at Piton in Somerset, Michael had left home at the age of seventeen in 1952 and opted for a career at sea in the Merchant Navy.

Rather than work on the family farm at Piton in Somerset, Michael had left home at the age of seventeen in 1952 and opted for a career at sea in the Merchant Navy.

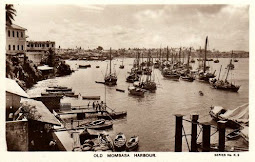

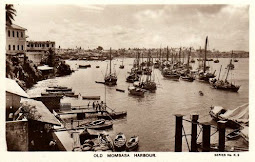

He recalled : "My mother thought going to sea would be good for me, but I don't think she imagined what I would witness. I'll never forget the time we docked in Mombasa. The Chief Officer came up to me and said : .png) "Eavis, we haven't got any crew, go and find them." I said : "Where do I go?" and he said : "The brothels and jails." I was only 17. So he gave me all this money and I wandered through the streets of Mombasa with a nice, fairly smart uniform on. A little girl came up to me and flighted her dress up at me and asked : "Would I lie with her ?" I don't know how old she was, probably about 13, so I said : "Thanks very much for the offer, but no thank you. But can you tell me where you would lie?", which of course was the brothel. So she took me into the brothel. They were all in there and I hauled them out".

"Eavis, we haven't got any crew, go and find them." I said : "Where do I go?" and he said : "The brothels and jails." I was only 17. So he gave me all this money and I wandered through the streets of Mombasa with a nice, fairly smart uniform on. A little girl came up to me and flighted her dress up at me and asked : "Would I lie with her ?" I don't know how old she was, probably about 13, so I said : "Thanks very much for the offer, but no thank you. But can you tell me where you would lie?", which of course was the brothel. So she took me into the brothel. They were all in there and I hauled them out".His life at sea only lasted for two years and he said : "When I was 19, my father died of stomach cancer and I had to come home and run the farm. The farm had always been a love of mine. The bank manager said : "Look, are you going to get stuck in because otherwise we'll sell the farm." I said : "No, you can't do that. I'll get stuck in and see what I can do".

.jpg)

Sixteen years were to pass before the seed of the idea of the farm being used to accommodate an 'al fresco' music festival was planted in 1969 on the day that Michael sneaked through a hedge with his future wife, Jean, to enter the 'Bath Festival of Blues'. (link) He was inspired, in particular, by the performance of Led Zeppelin to host a free festival on his farm the following year. He said : "Something flashes down and you suddenly change. Bit like St Paul; do you know what I mean? There's a change of attitude, a change of purpose". (link)

Sixteen years were to pass before the seed of the idea of the farm being used to accommodate an 'al fresco' music festival was planted in 1969 on the day that Michael sneaked through a hedge with his future wife, Jean, to enter the 'Bath Festival of Blues'. (link) He was inspired, in particular, by the performance of Led Zeppelin to host a free festival on his farm the following year. He said : "Something flashes down and you suddenly change. Bit like St Paul; do you know what I mean? There's a change of attitude, a change of purpose". (link)

Michael recalled : "I'd been into pop music all my life. I started with Pee Wee Hunt, Elvis Presley and Bill Haley but by the late 60s it was Dylan and Van Morrison and I was very anti the Vietnam war. Anyway, I had such a good time at the Bath Blues Festival in 1969 that when I got home I thought, 'We've got a good site here in Pilton. Why don't we do something similar?' The first problem was that I knew nothing about the music business. I started by ringing up the Colston Hall in Bristol to ask how I could get in touch with pop groups. A chap there gave me the name of an agent, and the agent put me in touch with the Kinks, who agreed to appear for £500, which was a lot of money for me to pull out of a milk churn". In addition, there was local opposition and he said : "I knew I was in for a fight, but my background has always been nonconformist. Our whole family down the years have been Quakers, Methodists, very anti-establishment, always looking dubiously at central government".

Right from the start Michael was conscious that the future spirit of Glastonbury was shaped as a reflection of the Eavis family life . He said : "The thing about the Glastonbury attitude was that the ethos came from the dining-room table at Worthy farm. The whole thing has always been very homegrown, so it does have an appeal and it is a family affair". Witness the fact that Emily, his youngest daughter, is now his co-organiser of the Festival. "They're all involved and everybody knows who we are and what we stand for, and we're not ripping people off. I like to think that I have passed that social conscience on to subsequent generations".

"Once I was sure I was going to do it, I realised we needed a stage. I got a local house-builder to put something together out of scaffolding and plywood. I asked him : "What would happen if a high wind came along, would it blow away?" He shook his head and said he didn't really know. None of us knew. So I got him to lash it to two apple trees with some hefty ropes. Another problem was accommodation. Where, on a farm, were we going to put up all these bands and their crews? Luckily, I got a couple of my neighbours to agree to let us use their cottages for the weekend.

"A week or so before the big day, I had a call from this fellow with a rich local Somerset accent. He sounded very genuine, offering to do security for the festival at two pounds per hour per person. That seemed very reasonable, so I agreed. When the day dawned, he and his mates turned up and they were the ugliest lot of Hell's Angels you've ever seen. What a fright I got. But I had agreed, so I had to take them on. When the fans started to arrive I immediately felt a lot better. These were softly spoken, middle-class hippies. Nice, attractive, interestingly dressed people. I found them very appealing. I felt right away that this was the beginning of something that would change our way of life".

For that first festival in the Autumn of 1970, 'The Kinks', were booked to top the bill, but dropped out after 'Melody Maker' printed a piece describing it as a 'mini-festival' and they were replaced at the last minute by Marc Bolan (link). Michael also had Al Stewart and 'Quintessence' on the bill (link) and said :

.jpg) " I regarded the whole event as kind of a cross between a harvest festival and a pop festival, so I had some bales of hay up on the stage and Marc Bolan perched on one of them when he was singing 'Deborah'. Despite my first encounter with him, I have to say that he was wonderful, easily the highlight of the Festival. The sun was going down behind the stage, a red sun. There were only 1,500 people there to see it, but you knew this was music that was going to last. To this day, I reckon it's one of the best things that ever happened here". (link)

" I regarded the whole event as kind of a cross between a harvest festival and a pop festival, so I had some bales of hay up on the stage and Marc Bolan perched on one of them when he was singing 'Deborah'. Despite my first encounter with him, I have to say that he was wonderful, easily the highlight of the Festival. The sun was going down behind the stage, a red sun. There were only 1,500 people there to see it, but you knew this was music that was going to last. To this day, I reckon it's one of the best things that ever happened here". (link)

Those 1,500 people had paid £1 for a ticket, including free milk from the farm and Michael made a loss of £1,500. During the rest of the 1970s, each meeting consisted of a series of informal events, culminating in the "impromptu" festival of 1978, when travellers flushed out from Stonehenge sought spontaneous entertainment.

.jpg)

Michael told the New Statesman that his hero in adult life had been the historian, writer, socialist and peace campaigner, E.P. Thompson and : "His speech from the Pyramid Stage in 1983 is still the best speech ever at Glastonbury". The late historian and peace campaigner likened the crowd to a medieval army and argued : “With its tents, all over the fields this has not only been a nation of money-makers and imperialists, it has been a nation of inventors, of writers of activists, artists, theatres and musicians". Looking directly at the assembled crowds he told them : “It is this alternative nation which I can see in front of me now”.

The 1990s, saw the Festival moved into the consumer-savvy age of cash machines, retail outlets, restaurants and flush lavatories. Channel 4 televised it, attendances topped 100,000 and the likes of Oasis, Blur and Robbie Williams headlined. Perhaps the defining image of the Festival for many was fixed in 1997, when torrential rain brought the 'Year of the Mud'.

After recovering from stomach cancer, Michael stood as a parliamentary candidate for the Labour Party in the 1997 General Election and polled over 10,000 votes. He then suggested that disillusioned Labour voters should switch their vote to the Green Party to protest at the Iraq War. In 2009, he was nominated by 'Time Magazine' as one of the 'Top 100 Most Influential People in the World' and in 2010, at the Festival's 40th anniversary, appeared on the main stage with headline artist Stevie Wonder to sing the chorus of "Happy Birthday". (link)He started the Festival with a £5,000 overdraft and by 2013 it was up to £1.3m and when asked : "Could he pay it off?" he said : "I'd feel guilty if I did. Isn't it funny? Why? We give away £2m a year to Greenpeace, Water Aid, Oxfam, we do local stuff at schools and housing. It's really important to keep that going. I can't just pay off my overdraft and say, 'Sod that".

He still continued to see himself as a farmer first and foremost and easier to reconcile with his Methodism : "Being a farmer is more authentic than organising Glastonbury. You're rearing cattle, you're feeding people. There's no branding, no sales pitch, it's just a natural way of living. There's no contamination, no transport, trains or planes. The festival has got a lot of other stuff – drugs, drinking, branding. It's a different thing. I love the Festival. That's why it's so successful – because I love it so much. But you offered me a preference, and I'm just telling you why I prefer the farm."

.jpg)

Michael said :

"I'm a bit of a Puritan, but I do enjoy myself immensely. I have a hell of a good time. I've got the best life anyone could possibly have. I'm not moaning. This whole Festival thing is better than alcohol, better than drugs. It's marvellous".

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)