Marcus, who has died at the age of fifty-four, had,.png) in his twenty year writing career, written more than 40 books for children and adults and in the process thrilled hundreds of thousands of readers young and old. (link) His work was shortlisted for more than 30 awards, including five nominations for the 'Carnegie Medal', two for the 'Edgar Allan Poe Award' and four for the 'Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize'. He also won the 'Branford Boase Award' for his debut novel, 'Floodland' and the 'Booktrust Teenage Prize' for 'My Swordhand Is Singing'. (link)

in his twenty year writing career, written more than 40 books for children and adults and in the process thrilled hundreds of thousands of readers young and old. (link) His work was shortlisted for more than 30 awards, including five nominations for the 'Carnegie Medal', two for the 'Edgar Allan Poe Award' and four for the 'Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize'. He also won the 'Branford Boase Award' for his debut novel, 'Floodland' and the 'Booktrust Teenage Prize' for 'My Swordhand Is Singing'. (link)

He was born at home in the village of Preston on the Isle of Thanet in East Kent, in the early summer of 1968 and was raised there with his elder brother Julian. The Isle is a 48 square mile area which was once separated from the mainland by the Wantsum Channel  is no longer an island. The sense of place obviously imprinted itself on the young Marcus and he recalled : "My very first memory is that I was being wheeled in my push-chair by my nanny through the church yard in the village where I grew up, a 12th century church yard in Kent. I remember the conkers falling because it was that time of year and the gravestones and the sunlight, even though it was cold and I don’t know why but that memory always holds a fascination with me". Later, in his books there would be a lot of what Marcus called : 'Running around in graveyards'.

is no longer an island. The sense of place obviously imprinted itself on the young Marcus and he recalled : "My very first memory is that I was being wheeled in my push-chair by my nanny through the church yard in the village where I grew up, a 12th century church yard in Kent. I remember the conkers falling because it was that time of year and the gravestones and the sunlight, even though it was cold and I don’t know why but that memory always holds a fascination with me". Later, in his books there would be a lot of what Marcus called : 'Running around in graveyards'.

Marcus recalled : "We were taught to treat books with reverence. You would never put a book on the floor, you'd never break its spine, you'd never write in a book. Dad would always give us a book every birthday and Christmas and it was almost symbolic – you must have a book, it's an important thing". In addition, there were several Bibles around the house and Marcus would later use his father's battered old leather one as the model for the Bible that featured in his story, 'Revolver'. There were also masses of material about William Blake, including a precious facsimile copy of 'Jerusalem' in a box file with 'Blake Jerusalem', written down the side. Marcus later recalled : "I thought William Blake was God. I thought that was God's name until I was about nine. There was a lot of religious imagery seeping off these shelves".

In 1975 when he was seven and doubtless educated in the village school, Marcus said that he : "Wanted to be a cat burglar, like 'The Pink Panther', but by the time I was eight I realised 'a', it’s not a proper job, and 'b', it’s illegal". Revealingly, when asked : "What do you think your school aged self would think of the present day you? Marcus replied : "I have no idea at all. I hope he’d like me, but I know he’d be too scared and shy to speak to me, so I don’t think he’d ever find out. Most likely he’d run the other way".

When he reflected on these years he said : "The seventies was a very strange and intense time, full of lots of weird television programmes and I used to collect this strange magazine every week called 'The Unexplained', that was full of stories about things like Loch Ness or ghosts or other weird phenomena." Also : "I was eight years old and very clearly remember the huge drought that happened, and it was really striking and the memories you have from first years of life are really powerful"."It really was severe. People ran out of water and had to go to the end of the street having to collect water from water bowsers". Forty-five years later, Marcus would use these ideas in his 2021 publication, 'Dark Peak'. (link)

When he reflected on these years he said : "The seventies was a very strange and intense time, full of lots of weird television programmes and I used to collect this strange magazine every week called 'The Unexplained', that was full of stories about things like Loch Ness or ghosts or other weird phenomena." Also : "I was eight years old and very clearly remember the huge drought that happened, and it was really striking and the memories you have from first years of life are really powerful"."It really was severe. People ran out of water and had to go to the end of the street having to collect water from water bowsers". Forty-five years later, Marcus would use these ideas in his 2021 publication, 'Dark Peak'. (link)

When asked :  "When you think about your childhood, what book comes to mind?" Marcus replied : "The Dark is Rising by Susan Cooper" the 1973 children's fantasy novel in which the eleven year old Will discovers he is one of a group of an ancient magical people, the 'Old Ones' who are waging a centuries-long battle against the forces of "the Dark" whose evil power is rising. He said : “More than anything else it was the imagery, the atmosphere of a sinister and snowy English winter, that grabbed me,”

"When you think about your childhood, what book comes to mind?" Marcus replied : "The Dark is Rising by Susan Cooper" the 1973 children's fantasy novel in which the eleven year old Will discovers he is one of a group of an ancient magical people, the 'Old Ones' who are waging a centuries-long battle against the forces of "the Dark" whose evil power is rising. He said : “More than anything else it was the imagery, the atmosphere of a sinister and snowy English winter, that grabbed me,”

Marcus said : "I did little sport as a teenager, but I read a lot. I was one of those teens who didn’t cause their parents any problems. I sat in my room, listening to music and reading. The most important book of my life then, was the 'Gormenghast Trilogy' by Mervyn Peake. That certainly changed my life, and I have my Dad to thank for introducing them to me".

Having himself passed his 11+ examination, in 1979 he followed in Julian's footsteps and began his secondary education at 'The Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys' in Canterbury, Kent with its motto 'Meliora Sequamur / May we follow better things'. It was probably at this time that his young hopes of becoming a writer were crushed by the adult observation that he should forget about that as an ambition, hard to achieve and with little money in it.

He described his experience at his new school, which still had its Army Cadets, as : "Pretty traumatic" and said "I went to a type of English school called a Grammar School. These are typically old establishments. Mine was founded in 1563 and that’s by no means the oldest and very often, in the ’80s, when I was there, they were still stuck in the past. Violence came from not just the other boys, it was a single sex school, but from the masters too and though being beaten up or hit with a hockey stick was bad, it was the psychological torture that was worse. The school seemed to almost condone such matters. We were told it was “character building,” but it certainly didn’t work for a timid, shy, weak young boy. The whole thing was pretty rough with the exception of two teachers who made life tolerable, so my mental energies were pointed in the direction of home, where I was much, much happier. I am lucky to have come from a truly loving family".

Marcus described himself as a teenager as : "Gawky, spotty, shy, timid, scared, shy and nervous" and said : "I had no idea what I wanted to be when I was a teenager. That worried me I think. I had no idea what life was about, what it could be about, what I wanted, what there even was to think about doing. I found the thought of the adult world very frightening, and still do, in many ways. I had no idea about how things work. Things like jobs, money, insurance, mortgages, etc. etc. The adult world seemed so complicated but to be honest, I was just struggling with being a teenager to worry too much about the years to come".

Marcus recalled : "As an older teenager, music began to be really important to me. I was a first-generation Goth, I think because it felt more real to me than the commercial pap of the mainstream, plus the music was great and the look. My first ever gig wasn’t 'goth' though, but 'The Smiths' and that probably was a major boost to me. It set me on a course of going to loads of concerts".As he said : "I have great memories of gigs by 'Siouxsie and the Banshees', 'The Sisters of Mercy' and so on. The first band I ever saw however, and still one of the best gigs of all time for me, was 'The Smiths' (link) in their first year of success. It was a mind-changing evening".

He also said : "I was also, and still am, very much into classical music. It was Mozart and Wagner back then. Wagner became Mahler as I grew older, and nowadays, it’s Richard Strauss, who I believe has composed the most sublime music of all time, with the possible exception of Chopin". Music was to inspire many parts of his books, including the chapter titles in 'White Crow' (link) and : “Much of the 'Book of Dead Days' which was inspired by Schubert’s epic song cycle, 'Winterreise' ”. (link)

"Music is something I love almost more than I love words. It’s a close fight between the two. But rather than let it be a fight, I have tried to let music into my head to colour my imagination and to stir my thoughts. I love (almost) all forms of music. It is my belief that the very best of any genre is worth listening to, and as to what it is that resonates for me. It has to be something that is authentic". "When I’m writing, I play the music that feels like what I am trying to put down on paper, whether that’s happiness or melancholy. I was a first generation Goth, and I loved it, The music was intense and the lyrics were dark, and it actually, for all its pretentiousness, meant something".

In 1984, when he was sixteen, his brother Julian, left home and took himself off the University of Cambridge University as an undergarduate reading Oriental Studies and Philosophy and would go on to work as a bookseller, painter, therapist and researcher for film and TV. His first book for children ‘Mysterium : The Black Dragon’ would be published in 2013 and win the 'Rotherham Children’s Book Award'. Marcus recalled that 1984 was also the year that he wrote his first story and said : "Every boy had to in the fifth form, that’s to say tenth grade, roughly. Mine was called 'Aaron’s Journey' and was sub-Moorcock, because that’s who I was mostly reading at the time". Michael Moorcroft was best-known for science fiction and fantasy, In 1986 at the age of eighteen, Marcus himself left home to start life as an undergraduate studying Mathematics at Bath University and said, in relation to his development : "On the very day that I arrived at University, I decided that I couldn’t go on being so shy", which he found so painful and disabling that : "It stopped me from doing almost anything, from answering the phone to making friends to speaking to girls etc. etc. On that day, as I arrived at University, I decided that I would pretend I wasn’t shy. No one knew me. I could reinvent myself. So I did. And after about three months went by, I realized I was no longer shy. I was normal. Which is to say, shy sometimes, confident others, sad, then happy, then calm, then excited, but no longer was I permanently disabled by shyness".(link)

When it came to his choice of subject he said : "I don't particularly feel I 'chose'. I lasted one year of a Maths degree, but we didn't see a number all year. It was so esoteric. I switched to the most interesting course I could find - 'Politics' ". He was in his second year when he was shaken by the death of his father at the age of seventy-four. He later summed up these years by saying : "The significant thing that happened was that I went to university still not knowing what I wanted to do and when I left university I still didn't know, so I went to work in a bookshop, because I liked books and it was a nice environment and that was the trigger for me thinking 'real people write these books'. So that made me realise that real living people write books and they get sold in bookshops so I started to try writing myself".

.jpg)

He left the bookshop,

Heffers in Cambridge after three

years and moved into publishing where he said : "I didn't really feel like I fitted in. Not at first anyway". However, this didn't seem to stop him from holding down his publishing job for ten years whilst writing his novels at the weekends.

"It took me a few years and I wrote a few books which weren't published, but they got me an agent and then the big, whole novel that I wrote was the first one that my agent sent off to Orion who I've been with ever since". Marcus said : “

I taught myself to write, by writing four books that remain unpublished. The first was terrible. The fifth book I wrote got published, won an award”. This was

'Floodland', with its school edition published in 2002, but it wasn't until he was forty-two that he was able to say to his interviewer, Callum Graham in 2010 :

"Only recently did I feel I could give up the day job". Of his new independence he said he liked : "The writing part. It's because you are getting paid for the strange thoughts in your head. You think of something and put it down on paper, and then people are buying it. That's something I still haven't actually got over".

In 2003 his 'Cowards' was published, an homage to his father, who had died fifteen years before. Marcus said, it was :

'About a group of British men during the First World War who had refused to fight. While many men objected on grounds of their conscience or religion to fight in the war, most accepted alternative roles, such as agricultural or medical work. A stubborn handful refused to do anything to further the war effort. One such group of 34 men, known as the Absolutists, were subsequently subjected to a round of brutal psychological and physical tortures. Finally, they were sent to France, where, military law being in force, they had the death sentence passed against them. Although it was immediately commuted to penal servitude, many ended up dying of starvation or disease in a labour camp'. 'Both my father and my mother’s father were conscientious objectors in World War Two, a thing that, while hard, had become a right enshrined in law due to the actions of the stubborn 34 who’d seen it through to the bitter end a generation before'.

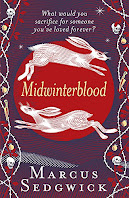

He said that his 2014 'Printz Award' winner, 'Midwinterblood',.jpg) included : “Lines by Nick Drake and Led Zeppelin…tucked away in the text, but the most significant source for the book is Stravinsky’s 'The Rite of Spring', which is probably the piece that made me fall in love with classical music, as well as modern music. (link) I first heard it at the age of around 14 and as the saying goes : 'It blew my tiny mind'. More energy than the Sex Pistols, freakier than Hendrix”.

included : “Lines by Nick Drake and Led Zeppelin…tucked away in the text, but the most significant source for the book is Stravinsky’s 'The Rite of Spring', which is probably the piece that made me fall in love with classical music, as well as modern music. (link) I first heard it at the age of around 14 and as the saying goes : 'It blew my tiny mind'. More energy than the Sex Pistols, freakier than Hendrix”.

Like much of his work, 'Midwinterblood' contained more than a little autobiographic material : 'Edward looks wistfully at Mat, and while the girls are pretty, Nancy particularly, it is Mat who he thinks about the most, because he wished he'd been more like Mat when he was young. If he'd been more like Mat, more confident, maybe he wouldn’t have missed his chances in life, chances that sometimes only came along once. Sometimes there are single moments, he thinks, where your path divides, your life can go one way, so very different from another. Work out well, rather than be a failure. And if you miss those chances, he thinks, well, is that it?'

When asked about what he enjoyed about his new independent life as a writer Marcus said : "Well that's hard, because it is just so fantastic! One thing is that you're your own boss. That's worth so much money to me. Because you are free to do whatever you want to do with your life on a daily basis and not having someone to crack the whip, and you're also not doing a job that you hate, which I have done before. That's the lifestyle part, but for the writing part it's because you are getting paid for the strange thoughts in your head. You think of something and put it down on paper, and then people are buying it. That's something I still haven't actually got over".

In 2013 when Marcus was forty-five years old he was struck down with a mysterious disease after a working trip to Asia and in 2019 wrote : 'I was rapidly given the (lack of) diagnosis that doctors call Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), or myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), and prescribed a course of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, to apparently fix whatever was wrong "in my head". You may not be surprised to learn that it didn’t work. Six years later, as the Salford bard put it, I am Still Ill'. (link)

In 2019 he returned to the theme of their father's conscientious objection  during the Second World War, 'Voyages in the Underworld of Orpheus Black'. He said : "It has a number of themes: the Orpheus legend of Ancient Greece; the dangers of futuristic, dehumanized, mechanized warfare; and the strained love between two brothers, one of whom has refused to fight in the Second World War". (link) It was to be his penultimate book and was followed by his last, 'Wrath', published this year. Cassie Cotton who could hear a noise that most people don't either notice or recognise and she believed was a sound that showed the Earth was in distress, damaged by human activity that was causing climate change. When her belief led to her being ridiculed and bullied at school, she disappeared. Her friend Fitz was determined to find her, but he had no idea where to start looking, or if he'd be in time to help her.

during the Second World War, 'Voyages in the Underworld of Orpheus Black'. He said : "It has a number of themes: the Orpheus legend of Ancient Greece; the dangers of futuristic, dehumanized, mechanized warfare; and the strained love between two brothers, one of whom has refused to fight in the Second World War". (link) It was to be his penultimate book and was followed by his last, 'Wrath', published this year. Cassie Cotton who could hear a noise that most people don't either notice or recognise and she believed was a sound that showed the Earth was in distress, damaged by human activity that was causing climate change. When her belief led to her being ridiculed and bullied at school, she disappeared. Her friend Fitz was determined to find her, but he had no idea where to start looking, or if he'd be in time to help her.

Marcus wrote :

'“You will never find it," his ghost says. "What?" "What you are looking for. You want to go back to the start. You want to go back to where you began. You want to find the happiness you once had. But you can never get there, because even if you somehow found it, you yourself would be different. You would have changed, from your journey alone, from the passing of time, if nothing else. You can never make it back to where you began, you can only ever climb another turn of the spiral stair. Forever” '.

'“You will never find it," his ghost says. "What?" "What you are looking for. You want to go back to the start. You want to go back to where you began. You want to find the happiness you once had. But you can never get there, because even if you somehow found it, you yourself would be different. You would have changed, from your journey alone, from the passing of time, if nothing else. You can never make it back to where you began, you can only ever climb another turn of the spiral stair. Forever” '. The Ghosts of Heaven

'People think I have so much faith in myself, but I have none. I have no faith in myself, or in what I can do, and yet people think I can do anything I want. That's how I seem, but it's an illusion. It's an act, nothing more'. She Is Not Invisible

.jpg) 'And if I really can see the future, then what does it mean? Is there any sense in our lives if everything is already out there, just waiting to happen? For if that were so, then life would be a horrible monster indeed, with no chance of escape from fate, from destiny. It would be like reading a book, but reading it backwards, from the final chapter down to chapter one, so that the end is already known to you.'

'And if I really can see the future, then what does it mean? Is there any sense in our lives if everything is already out there, just waiting to happen? For if that were so, then life would be a horrible monster indeed, with no chance of escape from fate, from destiny. It would be like reading a book, but reading it backwards, from the final chapter down to chapter one, so that the end is already known to you.'

The Foreshadowing

'Orwell's vision of our terrible future was that world-- the world in which books are banned or burned. Yet it is not the most terrifying world I can think of. I think instead of Huxley-- ...I think of his Brave New World. His vision was the more terrible, especially because now it appears to be rapidly coming true, whereas the world of 1984 did not. What's Huxley's horrific vision? It is a world where there is no need for books to be banned, because no one can be bothered to read one'. The Monsters We Deserve

'It was like a new kind of vision, seeing with eyes as keen as scalpel blades, that cut away desires and emotions and wishful thinking and left only what was fact'.The Dark Flight Down

'Edward looks wistfully at Mat, and while the girls are pretty, Nancy particularly, it is Mat who he thinks about the most, because he wished he'd been more like Mat when he was young. If he'd been more like Mat, more confident, maybe he wouldn’t have missed his chances in life, chances that sometimes only came along once. Sometimes there are single moments, he thinks, where your path divides, your life can go one way, so very different from another. Work out well, rather than be a failure. And if you miss those chances, he thinks, well, is that it?'

'Edward looks wistfully at Mat, and while the girls are pretty, Nancy particularly, it is Mat who he thinks about the most, because he wished he'd been more like Mat when he was young. If he'd been more like Mat, more confident, maybe he wouldn’t have missed his chances in life, chances that sometimes only came along once. Sometimes there are single moments, he thinks, where your path divides, your life can go one way, so very different from another. Work out well, rather than be a failure. And if you miss those chances, he thinks, well, is that it?'Midwinterblood

'Even the dead tell stories'.

'He wonders if a few moments of utter and total joy can be worth a lifetime of struggle.

Maybe, he thinks. Maybe, if they're the right moments'.

Midwinterblood

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)