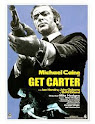

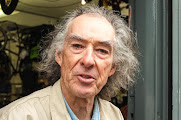

Mike, who has died at the age of ninety had a long and varied career in the media as a screenwriter, television director, playwright and novelist, but it was, at the age of thirty-nine in 1971, as the director of the big screen movie, 'Get Carter', that he will best be remembered. (link) The creation of the film was coloured by his life-changing experience of two years National Service in the Royal Navy which left him highly critical of the corruption in 1970's Britain and and its execution, by the skills and working methods Mike had gained from his earlier career in television.

Mike, who has died at the age of ninety had a long and varied career in the media as a screenwriter, television director, playwright and novelist, but it was, at the age of thirty-nine in 1971, as the director of the big screen movie, 'Get Carter', that he will best be remembered. (link) The creation of the film was coloured by his life-changing experience of two years National Service in the Royal Navy which left him highly critical of the corruption in 1970's Britain and and its execution, by the skills and working methods Mike had gained from his earlier career in television.

* * * * * *

Mike was born in Bristol in the summer of 1932 and grew up in a middle class, semi-detached house in a cul de sac, the son and only child of Norah and Graham who worked for the Will's Tobacco Company as a commercial traveler. As a result of the itinerant nature of Graham's work, the family moved to Yeolvil and then to Salisbury and it in that cathedral city that Mike spent his formative years. Norah was a devout catholic and as there was no catholic school in Salisbury, at the age of seven Mike began to attend Prior Park College as a boarder, twelve miles away in Bath.

It was here that Mike first became smitten by the movies and recalled : "In the winter and autumn months, there was one film every fortnight, which was an absolutely magical experience. The first one was 'Top Hat' with Fred Astaire". "You got enamored. It seemed so magical". He was five years old and still in school in Salisbury w

.jpg) hen the movie directors Powell and Pressburger came to film scenes for 'The Return of the Scarlet Pimpernel' at Prior Park School. In later life Mike saw fit to add this to his own 'fascination with the movies' mythology when he said : "I didn't know who they were. Even so I cut some classes and got into terrible trouble, so I could watch what was going on". They obviously chose the school for location because of its Georgian grandeur. As time went on, when at home in Salisbury, he said he secretly sneaked out to watch films at the ABC Regal or Gaumont two or three times a week. In addition, he got involved in school amateur dramatics.

hen the movie directors Powell and Pressburger came to film scenes for 'The Return of the Scarlet Pimpernel' at Prior Park School. In later life Mike saw fit to add this to his own 'fascination with the movies' mythology when he said : "I didn't know who they were. Even so I cut some classes and got into terrible trouble, so I could watch what was going on". They obviously chose the school for location because of its Georgian grandeur. As time went on, when at home in Salisbury, he said he secretly sneaked out to watch films at the ABC Regal or Gaumont two or three times a week. In addition, he got involved in school amateur dramatics.When interviewed in 1998 Mike said of that the school was run by the Irish Christian Brothers : "Who are pretty renowned religious thugs. So it was a curious education really. I escaped from there at the age of fifteen having got to the age of matriculation with a distinction in 'Mathematics' and a credit in 'French'. I had wanted to get into the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts to do the stage management course, but my parents couldn't conceive of me doing anything like that. I mean, I was obsessed by the cinema already. Because I's got this distinction in Mathematics they had decided that I'd be articled to a chartered accountants. That's what I did at fifteen".

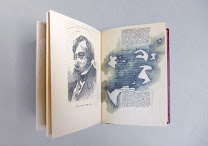

.jpg) His firm was was the Dickensian sounding 'Fawcett, Brown and Pinniger' and with them until the age of twenty, he had followed a five year correspondence course in accountancy which he said he had "not liked at all" and he qualified at a second take at his exams at the age of twenty-two in 1954. He now had to undertake his two years National Service in the Royal Navy and said : "I applied to the Navy and got in and to my parents horror turned down a commission as an officer". He did this because that : "I was likely to be stuck in a barracks. So I went on the lower deck which was the most important thing I ever did, probably in my life, because it was a complete revelation to me. A complete education".He served on two mine sweepers, HMS Coquette and Wave and was recognised as an 'Able Seaman' when he left two years later.

His firm was was the Dickensian sounding 'Fawcett, Brown and Pinniger' and with them until the age of twenty, he had followed a five year correspondence course in accountancy which he said he had "not liked at all" and he qualified at a second take at his exams at the age of twenty-two in 1954. He now had to undertake his two years National Service in the Royal Navy and said : "I applied to the Navy and got in and to my parents horror turned down a commission as an officer". He did this because that : "I was likely to be stuck in a barracks. So I went on the lower deck which was the most important thing I ever did, probably in my life, because it was a complete revelation to me. A complete education".He served on two mine sweepers, HMS Coquette and Wave and was recognised as an 'Able Seaman' when he left two years later.

The whole experience had a profound effect on Mike who said : "As a rating, an Ordinary Seamen, I was free to explore every corner of every impoverished fishing port around these Islands. Clad in my bellbottoms, blue collar and white cap, I witnessed scenes of such Hogarthian depravation that I experienced a sort of epiphany. From being a young Tory and recently-qualified Chartered Accountant, I became a passionate Socialist".

It was 1956 and he now went to London and for a time lived off the expenses he got for applying for jobs as a chartered accountant and then got a foot in the door of the new and coming medium of television broadcasting and got a job as a teleprompter using the new American device which came with the advent of commercial and live tv. Mike said : "The advantage was that you worked with every single company - Granada, BBC, ATV. ABC. So you were going round all over the place. It was an immense experience working in a vast studio. Fears fell away. In addition to which you were able to observe so much what was going on. It was an amazing curve for me".

In his spare time he now wrote scripts for TV advertising magazines and made enough money to allow him, after two years, to leave work as a teleprompter. He now became the editor of ATV's 'Sunday Break' which had been designed for a young audience and which he now changed by taking out the music and steering it towards the more serious subjects such as gambling and alcoholism. This was followed by him landing the job as a writer for 'World in Action', the weighty investigative current affairs programme made by Granada Television for ITV and his scripting, at the age of thirty-one, in 1963, 'The British Way of Death'.

Mike made the jump to film director when, in 1969 he directed an episode for 'ITV Playhouse', 'Suspect' in which a proud woman coldly concentrates on keeping up appearances when her 50-year old husband and a young schoolgirl go missing at the same time. The following year came 'Rumour' in which a hard-bitten newspaper reporter is drawn back into the world of sleaze he had hoped to have left behind.

Mike recalled : "In those days there were only three television channels so the

audiences were huge. Consequently your profile could, if all went well, be pretty high. Feature producers watched out for any emerging talents. Presumably because they were cheaper than established directors but also because there was a certain kudos to finding new contenders". He was spotted by Michael Klinger who had earlier spotted Roman Polanski who made his first English films, 'Cul-de-sac' and 'Repulsion' with him. Mike said : "When Klinger sent me 'Jack’s Return Home', a novel by Ted Lewis, and asked if I wanted to adapt and direct it as a feature film, I couldn’t resist".

audiences were huge. Consequently your profile could, if all went well, be pretty high. Feature producers watched out for any emerging talents. Presumably because they were cheaper than established directors but also because there was a certain kudos to finding new contenders". He was spotted by Michael Klinger who had earlier spotted Roman Polanski who made his first English films, 'Cul-de-sac' and 'Repulsion' with him. Mike said : "When Klinger sent me 'Jack’s Return Home', a novel by Ted Lewis, and asked if I wanted to adapt and direct it as a feature film, I couldn’t resist". "It rang all sorts of bells with me because Jack Carter, he's going up North to investigate the dubious death of his brother. The were scenes in pubs and clubs and lots of strange places that I recognised from my days in the Navy. So I knew instinctively the kind of milieu that he was moving in because I was on the lower decks and when you went ashore, all these ports, like Hull and Grimsby, are the kinds of places you ended up in and there was no where that would accept you. So I knew what the man was writing about". Harking back to younger days at sea, when he described himself as a 'passionate socialist', he said : "While not sharing the psychopathology of Jack Carter, I certainly shared his anger".

Mike brought the speed with he worked in television to the production and writing the script, casting it, finding the locations and shooting it took only 32 weeks. He said : "Michael Caine's name was never mentioned initially. Once he'd seen the first draft, he quickly came round frankly I was surprised because Carter was such a shit. I mean he's such an unpleasant men that I couldn't conceive a star taking the role". Mike spent four days with Michael Caine and his chauffer driven Cadillac, looking at possible film locations and focused on Newcastle and North Shields and began to fit the novel to Newcastle where he said : "As soon as I saw those huge rust-coloured bridges stretching across the Tyne I knew this was Jack’s manor".

Mike said that given the deprived nature of the locations they stopped at made him, sitting in luxury in the back of the Cadillac, a little uncomfortable. Without rancour he said that from a total budget of £750,000 : "Michael was paid £100,000 and a big percentage. I got £8,000 for writing and directing and no percentage".When it came to the inspired casting of John Osborne, playwright, screenwriter and actor most famous for his 1956 stage play, 'Look Back in Anger' as the gangster Cyril Kinnear Mike said : "My agent at the time was also Osborne’s and, out of the blue, he suggested him. We met and liked each other. John’s talent for invective intimated that there was another side to him than the affable playwright. You’re right. Chris Wangler, my brilliant sound recordist, asked for John to project more. I resisted his pleas and simply moved the camera closer. John’s decision to speak quietly was clever. So mundane; so sinister". When it came to playing the card scene he said : "It was the toughest scene I had to shoot. Boxing myself in by setting it in a bay window made it even harder for all concerned. I covered it to the best of my abilities, and being forced to move closer and closer on Kinnear, helped me in the end". (link)

Quotations :

To Cliff Brumby : "You're a big man, but you're out of shape. With me ? It's a full time job. Now behave yourself".

To Albert : "I know you didn't kill him. I know".

Mike was philosophical about the fate of his greatest film and said : "Soon after its release in 1972, the film was banished to the dark shadows of cult status. It was, after all, not considered a very nice film here in the UK. But then most of my films have been more appreciated beyond these shores, particularly in the US and France. That changed when, in 2009, the BFI decided to release it again; albeit in a limited way. This time around I think British audiences found the endemic corruption intimated in its every frame more acceptable. By then their rose-tinted glasses were off. We no longer saw our country as a beacon of propriety, and law and order. Our parliamentarians, police, press, the whole damned edifice, had been found to be wanting. They all had their noses in the money trough. The cancer of greed had reached every organ of British society. Maybe, just maybe, Get Carter had been an accidental augury? " (link)

Mike once said :

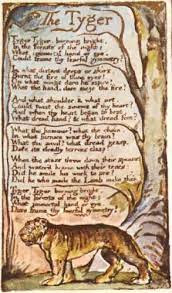

"Mordant humour has always attracted me. Being indoctrinated a Roman Catholic at an early age has left me with the “grim reaper” as my constant companion. The only way I can cope is to laugh at him". (link)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

%20(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(3).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)