.jpg) Artists Advisory Committee' to cover the Second World War, and the first to die on active service, in a plane crash in 1942. He was thirty-nine. Now, to mark the 80th anniversary of his death, a full length feature documentary, 'Drawn to War', told in his own words, through previously unseen private correspondence, is to be shown at selected cinemas around Britain. (link)

Artists Advisory Committee' to cover the Second World War, and the first to die on active service, in a plane crash in 1942. He was thirty-nine. Now, to mark the 80th anniversary of his death, a full length feature documentary, 'Drawn to War', told in his own words, through previously unseen private correspondence, is to be shown at selected cinemas around Britain. (link).png) His relegation to obscurity was probably hastened by the fact that, at the time of his death, one great mural, at Waterloo's Morley College, painted by Eric and fellow artist, Edward Bawden and unveiled by the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin in 1930, had been destroyed in 1940 in the London Blitz. In addition, some of his war paintings had been censored and therefore never seen and dozens more had been lost at sea on their way to an exhibition on the art of propaganda in South America.

His relegation to obscurity was probably hastened by the fact that, at the time of his death, one great mural, at Waterloo's Morley College, painted by Eric and fellow artist, Edward Bawden and unveiled by the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin in 1930, had been destroyed in 1940 in the London Blitz. In addition, some of his war paintings had been censored and therefore never seen and dozens more had been lost at sea on their way to an exhibition on the art of propaganda in South America.

Eric was born in the summer of 1903 in Acton, London, the youngest of four children, one of whom had died in infancy. His family were Methodists by religion and in his early years he was shaped by his mercurial, father, Frank, who was a lay preacher and more tranquil mother, Emily. They lived in rooms over Frank's cabinet maker's and upholsterer's shop at numbers 5 & 6, in the Parade, in Churchfield Road. While he was still a small child they moved to the seaside town of Eastbourne in Sussex, where his parents ran an antique shop.

In 1919, at the age of sixteen, Eric won a scholarship to Eastbourne School of Art and three years later he gained another, to the relatively new and as yet unsung 'Royal College of Art' in London and it was here that he became close friends with fellow student, Edward Bawden.

In 1919, at the age of sixteen, Eric won a scholarship to Eastbourne School of Art and three years later he gained another, to the relatively new and as yet unsung 'Royal College of Art' in London and it was here that he became close friends with fellow student, Edward Bawden.

In 1933 Eric and Tirzah painted murals at the Midland Hotel in Morecambe and that November, he held his first solo exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery in London and sold twenty of the thirty seven works displayed.

His 1936 Exhibition was well reviewed in both the 'Observer' and the 'Sunday Times'. The Observer critic, Eric Newton, reported : 'I had never realised the wiriness of wire netting before looking at his 'Cliffs in March'. With few exceptions each of his watercolours contains a new revelation of this kind'. In the same year Michael Rothenstein painted Eric and Edward Bawden, which was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2012.

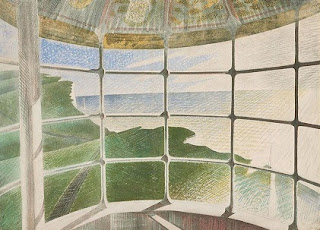

Eric and Tirzah lodged in 'Brick House' in Saffron Waldron, Essex, with Edward and his wife until 1934, when they purchased 'Bank House' at Castle Hedingham, Essex. In her autobiography, 'Long Live Great Bardfield', Tirzah was open and never self-pitying about the impact on her of the affair that Eric publicly pursued with the artist Diana Low, starting while she was pregnant with the first of their three children.His fascination with the East Sussex countryside which started in his youth, remained unabated and he said : 'The lighthouse at Beachy Head, an immense bar of light on the sea, is splendid and must be done'.(link)

' How I love the South Downs in winter. I love its definite shapes its bleached greens and brown, so attuned to the starved brush of my water colours'.(link)

'I long to walk the chalk paths. Those long white roads are a temptation. What quests they propose. They take us away to the thin air of the future or to the underworld of the past'. (link)

Ravilious expert, James Russell said : "His favourite time of day as an artist was the very early morning. He would get up in the very early morning, preferably in the winter and capture that cool luminous quality of the light in the early morning".(link)

In 1936 Eric and Edward were both active in the campaign by the 'Artists' International Association' to support the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War and prior to the outbreak of the Second World War and he loaned his work to the 1937 'Exhibition Artists Against Fascism'. With outbreak of the Second World War he considered joining the Army as a rifleman, but was deterred by friends and joined a Royal Observer Corps post in Hedingham. He was then accepted as a full-time salaried artist by the War Artists' Advisory Committee in December 1939. In the Spring of 1940 He was given the rank of 'Honorary Captain' in the Royal Marines and assigned to the Admiralty. He wrote :

'My dearest Tirzah, would you believe ? I've been made an Honorary Captain in the Royal Marines. I expect they will be presenting me with my own brigade of paintbrushes before this is out. It's a far cry from my days on the observation post at Sudbury Hill. It was more lovely than words can say, flying over the moors and coast today, in an open plane. Just floating on great curly clouds perfectly still and cool'. (link)

In February 1940, Eric reported to the Royal Naval barracks at Chatham Dockyard and while based there, he painted ships at the dockside and barrage balloons further down the River Medway at Sheerness.

His 'Dangerous Work at Low Tide', in 1940 depicted bomb disposal experts approaching a German magnetic mine in Kent on Whitstable Sands.

He wrote from near Norway in April 1940 of : “Bitter fighting” and : “How the sun has not shone much by day or night”. Tirzah replied to him with : “How terrifying it must be witnessing real war”. In May he sailed to Norway aboard 'HMS Highlander', which was escorting 'HMS Glorious' and the force being sent to recapture Narvik from the Germans. From the deck of Highlander, Eric painted scenes of both 'HMS Ark Royal' and 'HMS Glorious' in action.

His 'HMS Glorious in the Arctic' depicts Hawker Hurricanes and Gloster Gladiators landing on the deck of 'Glorious' as part of the evacuation of forces from Norway in June.

The following evening 'Glorious' was sunk, with the loss of 1,500 British sailors drowned. Tirzah wrote : “I’ll be so relieved to have you back”, adding that, back home, their son John : “Was almost hit by a bomb in a field”.

Eric wrote to Tirzah from 'HMS Highlander' ; 'The seas in the Arctic Circle are the finest blue you can imagine an intense cerulean and sometimes almost black. It was so nice working on deck long past midnight in bright sunshine. I enjoyed it a lot. Even the bombing, which is wonderful fireworks'. 'Next I will go to Iceland. It is the promised land'.(link)

.jpg) On returning from Norway, Eric was posted to Portsmouth from where he painted submarine interiors at Gosport and coastal defences at Newhaven. Despite the cramped conditions he loved to draw and paint and wrote to Tirzah : “It’s pandemonium with all the shelling and yet I feel a stir in me that it really is possible to like drawing war activities”.

On returning from Norway, Eric was posted to Portsmouth from where he painted submarine interiors at Gosport and coastal defences at Newhaven. Despite the cramped conditions he loved to draw and paint and wrote to Tirzah : “It’s pandemonium with all the shelling and yet I feel a stir in me that it really is possible to like drawing war activities”.

.jpg)

Tirzah gave birth to their daughter, Anne, in April 1941, but later that year wrote of a lump on her left breast. Anne later said: “My father asked to be transferred from Yorkshire, where he was then based, to Essex. My mother needed a mastectomy and then an abortion as it was not felt safe to have another child”. The family moved out of 'Bank House' to 'Ironbridge Farm' near Shalford, Essex.

In October 1941, Eric was transferred to Scotland, having spent six months based at Dover and first stayed with John Nash and his wife at their cottage on the Firth of Forth and painted convoy subjects from the signal station on the Isle of May. In addition, at the Royal Naval Air Station in Dundee, he drew, and sometimes flew in, the 'Supermarine Walrus Seaplanes' based there.

In mid-1942 Eric was posted to Iceland and Tirzah felt she could not stop him, though she knew that he might never return and he wrote to her : 'An unbelievable lunch of caviar, paté and cheese' and then described the island’s lunar-like craters and extolled the deep shadows and leaflike cracks of the subarctic landscape, before ending : 'Would you like a pair of gloves, sealskin with fur on the back? Draw around your hand on writing paper so I can get the size. Goodbye darling. Hope you feel well again'.

On 28 August 1942 he flew to Reykjavík and then travelled on to RAF Kaldadarnes and day he arrived there, 1 September, a Lockheed Hudson aircraft had failed to return from a patrol. The next morning three aircraft were dispatched at dawn to search for the missing plane and Eric opted to join one of the crews. The aircraft he was on also failed to return and after four days of further searching, the RAF declared that Eric and the four-man crew lost in action.Tirzah then had to write 49 times, over two years to the War Office, to get a widow’s pension, before it was accepted that her husband was not just 'missing' but 'formally dead'. It was all the more awful because she had been left with three youngsters and was experiencing deteriorating health. She was to die of cancer, in her 40s, in 1951.

Alan Bennet, in 'Drawn to War', said : "Being a war artist was not a soft option. Painting was Ravilious's active service - and he gave his life for it. Not quite a martyr's death, but it preserves and elevates him".

Tirzah wrote :

'Goodbye my love. The world will never know what future great works of art your departure has deprived it of'.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Love his work...thanks John

ReplyDelete