Her father worked as a porter at the Spitalfields Market and her mother was a cigar maker at Godfrey & Phillips in Commercial Street and she grew in Goulston Street which she remembered with no fond memories and said : "It was horrible, we had a little scullery, too small to swing a cat. My mother had one bedroom and, the three children, we slept in a put-you-up. I had two sisters Rebecca and Esther". Tragedy struck the family when her father died at the age of forty-four when she was thirteen years old . She recalled : "He used to take me everywhere, he was marvelous. He took to me to the West End to visit my aunt, she was an old lady with a parrot and lived on Berwick St. We used to have a laugh with the parrot".

When she was twelve in 1929, her school, Gravel Lane School, which she loved, closed down. She recalled : "It was lovely school, they taught us housewifery. We had a little flat in the school and we used to clean it out, then go shopping in Petticoat Lane to buy ingredients to make a dinner, imagining we were married. The boys used to do woodwork and learnt to make stools and things like that". Her next school, the Jewish Free School in Bell Lane, where she stayed until she was fourteen in 1932, was a different proposition and she said : "It was very strict and religious. When the teacher wanted us to be quiet, she’d say, ‘I’m waiting!" Nevertheless, she said : "It was good, I enjoyed my school life".

When she left school she got her first job in dressmaking, to which she was not best suited : "I used to lay out material. I do not know why but I must have heavy fingers, I could not manage the silk. It used to fall out of my hands. I only lasted a week before I left, I could not stand it". She then went to work with her sister Rebecca in Whitechapel and concentrated on : "Tailoring, men’s trousers, putting the buttons on with a machine. We worked long hours and it was hard work".

Beatty was in work, but in the 1930s Britain was hit by the worldwide economic slump caused by the Great Depression and thousands were out of work, particularly in already deprived urban areas such as the East End of London where there was much poverty and deprivation. This made the easily identifiable ‘Jewish community’ scapegoats for the worsening economic situation. Jews were blamed for ‘taking all our jobs’, driving down labour costs and being unscrupulous landlords, amongst a host of other accusations. Whitechapel in the East End became a volatile and dangerous place for young Jewish women like Beatty. Frustrated by the lack of opportunities around her, ground down by poverty and antisemitic abuse, she was desperate for change and, unusually for a working class woman, became fiercely political.

In 1932, when she was just fifteen, the former Labour and Conservative politician Oswald Mosley formed a far-right nationalist party, the British Union of Fascists (BUF), which openly encouraged its uniformed supporters to attack Jews. They distributed antisemitic leaflets and their ‘mob orators’, such as Mick Clarke and Owen Burke, night after night, sought to whip up violence on the street corners. Beatty said : "It was frightening to be walking around as a Jew in those days. People were getting beaten up. The Blackshirts used to rampage around the area and break the windows of Jewish shops and synagogues, it was very threatening".

.png)

The anti-fascist groups regularly met at No. 38 Osborn Street in Morris Curley and Rosie Kersch’s 'Curley’s Café' in Whitechapel from 1937, where the walls were hung with photographs of well-known local Jewish boxers and posters to raise funds for Communist causes in Russia. It was a small noisy, crowded café with a highly political clientele and many café regulars, including friends of Beatty, joined the International Brigades and went to Spain to fight in the Civil War which erupted in the summer of 1936 between the left-wing Republican government and General Franco’s fascist Nationalists. Beatty said : "The Civil War in Spain had a profound effect on British Jews. We were so moved by what was going on there –it was rousing, we were so involved, Many young Jewish men from Whitechapel joined up and went to fight; many did not come back".

War was on the horizon and terrible things were happening to the relatives of the East End Jewish community in Europe. Civil War was raging in Spain and internationally fascism was on the rise. It was against this background, during a night at Curley’s in 1936, that Beatty first heard about the planned march of Mosley and his uniformed Blackshirts through the heart of the Jewish East End. Beatty's immediate, furious response was : "We are not having that here!" She was one of over a hundred thousand people who signed a petition to prevent the march from taking place which was delivered to the Home Secretary, but to no avail. As a result, in the following weeks, trade unions, Socialist and Communist groups, along with the anti-fascists, distributed thousands of leaflets to workshops, cafés and meeting halls, synagogues and tenement blocks and to people on the street about the planned counter protest.

Early in the morning of 4 October 1936, the Communist Party vans were out with loudhailers driving around the streets. As, twenty years later, a twenty-five year old Arnold Wesker dramatised in his play 'Chicken Soup with Barley' (link), people were called out to join the protest :

"Man your posts! Men and women of the East End come out of your houses! The Blackshirts are marching! Come out! Come out!"

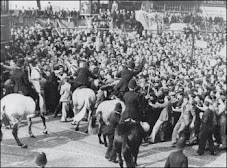

That morning, Beatty remembered leaving home with her best friend Ginny and said : "When we got to the top of Goulston Street, my God, there was millions of people there and they were all shouting. There was Irish and Jews, they come from everywhere to join us in the fight, along with women, men, children, just loads of people. You know when the Royal Family come down the streets, there was more people than that. Lots more. I was not frightened because there were hundreds of people there". In fact, nearly 300,000 joined the protest and many others were afraid and stayed indoors and put the shutters down.

As the Beatty and Ginny made their way to the meeting point near Aldgate pump, they saw a forest of red flags and banners rising from the crowd with the words : 'REMEMBER OLYMPIA' and ‘THEY SHALL NOT PASS'. More and more people poured into the area singing and shouting with a roar of noise and emotion.

As the Beatty and Ginny made their way to the meeting point near Aldgate pump, they saw a forest of red flags and banners rising from the crowd with the words : 'REMEMBER OLYMPIA' and ‘THEY SHALL NOT PASS'. More and more people poured into the area singing and shouting with a roar of noise and emotion.

Irish dockers, repaying Jewish support for their strike in 1912, joined the throng in their thousands, swarming into the streets armed with pick axes and were joined by Jewish workers from across the borough. Together they formed an impenetrable blockade at Gardiner’s Corner and the demonstrators shouted, "No Pasaran!" (They shall not pass), the battle cry used by anti-fascists in the Spanish Civil War, along with the slogan "Madrid today… London tomorrow".

Irish dockers, repaying Jewish support for their strike in 1912, joined the throng in their thousands, swarming into the streets armed with pick axes and were joined by Jewish workers from across the borough. Together they formed an impenetrable blockade at Gardiner’s Corner and the demonstrators shouted, "No Pasaran!" (They shall not pass), the battle cry used by anti-fascists in the Spanish Civil War, along with the slogan "Madrid today… London tomorrow".

Beatty described the atmosphere as "tense" but "absolutely electric". At first, she was not afraid, then suddenly the mood shifted. They heard screaming, the shrill sound of police whistles and loud cries somewhere near the front. The crowd was thrown into a state of fright and panic. As pandemonium took hold as the bulk of those assembled fled in one great streaming mass towards where the girls were standing. Mounted police had charged into the throng, indiscriminately hitting protestors with batons and under the great push of people Beatty and Ginny were squeezed ever closer against a shop window. They soon became tightly wedged, unable to move backwards or forwards. Under the tremendous pressure the large window shattered. Ginny fell through and cut her hand badly on a shard of glass. Beatty said : "It was terrifying. We had to go to hospital and get her stitched up" and hundreds of other injured protestors were at the London Hospital when they arrived. Others went to Curley’s Café or the Whitechapel Library, which had both temporarily become emergency first aid centres for the day. When the two of them left the hospital, the crowd at Gardiner’s Corner had largely dispersed, so they walked down to Cable Street together, where the protest had been re-routed. Beatty recalled : "There was a lorry overturned there and hundreds of people and little bits of fighting breaking out here and there, but not with the fascists - that happened in Aldgate. The fighting was with the police".

From Cable Street they walked to Royal Mint Street near the Tower of London, where the fascists had congregated in preparation for their march through the East End. There they saw an army of uniformed Blackshirts, banging drums and raising their arms in the Nazi salute. Beattie recalled : "They were all lined up in a row, thousands of them, with their black suits and jackboots on, waiting for Oswald Mosley to come". With fights and violent skirmishes breaking out everywhere Beattie said : "I was scared of them; they were lashing out at the crowd. They were dangerous, but thank God, I never got hurt. It was frightening, so I said to Ginny : "We’d better get away from here"".

They now made their way back through the crowds to Cable Street. By then a fierce street battle was raging between thousands of protestors and over 6,000 police officers, including the entire London mounted division. Barricades had been strengthened with corrugated iron, old mattresses and wooden planks. Protestors were hurling broken bottles, fireworks, paving stones, anything they could at the wall of mounted police. Irish and Jewish women living in the dilapidated houses lining the street were throwing buckets of water and emptying chamber pots, pelting the police from above. Repeated baton charges were made directly into the crowd, there were violent fights everywhere and nearly a hundred arrests made. Beatty said : "People were shouting and screaming, so many people, they were throwing marbles on the floor for the horses. I didn’t like that. My great friend, Charlie Goodman got arrested, he climbed up a lamppost. He was a communist, he went to prison for that for about a week".

.jpg)

.jpg) Max Levitas, who died on November 2018 aged 103 was the last survivor of the Battle of Cable Street and said : "The police force came with their horses to Cable Street, but they didn't get away with it. We stayed there even though people were knocked down with the batons and with the horses. All of a sudden we got a notice that the Government had met and decided that the Fascists would not march because if they did march, there would be deaths because the people around here had enough of them".(link)

Max Levitas, who died on November 2018 aged 103 was the last survivor of the Battle of Cable Street and said : "The police force came with their horses to Cable Street, but they didn't get away with it. We stayed there even though people were knocked down with the batons and with the horses. All of a sudden we got a notice that the Government had met and decided that the Fascists would not march because if they did march, there would be deaths because the people around here had enough of them".(link)Beatty recalled the events of the Battle of Cable Street eighty years later when she was ninety-nine years old in 2016. (link)

When she recalled her social life in the turbulent 1930s she said that as a member of the Labour League of Youth : "We used to go on rambles. It was lovely. We went to Southend once. I always used to march to Hyde Park on May Day and carry one of the ropes of our banner. I met my husband John in Victoria Park when I was with the Young Communists League, although I was not a member. They had a Sports Day and my husband was running for St Mary Stratford Atte Bowe because he was a Catholic. I met him and we went to a Labour Party dance. We got married in 1939. We managed to get a flat in the same building as my mother, at the top of the stairs. They were private flats and I remember standing outside with a banner saying, ‘DON'T PAY NO RENT' , because the owners would not do the flats up, they did not look after us. It was horrible thing for us to have to do, but it worked. I laugh now when I think about it. I was always brave. I am brave now". Beattie said this in 2018, when she was 101 years old.

With the outbreak of the Second World War and the German blitz of London Beatty said : "We got bombed out of those flats while my husband was in the army. I had a baby so they sent me to Oxford where my husband was based with the York & Lancasters. I came back to the East End to try to get a flat here and I got caught in one of the air raids, but I knew this was where I had to live. My mother used to get under the stairs in Wentworth St when there was a raid and put a baby’s pot on her head. The War was terrible". She said eventually : "We got a three bedroom flat at last, because I had two girls and a boy. I lived sixty-seven years there".

Beatty said that after the War :"My husband never earned much money so I had to carry on working. He had twenty-two shillings a week pension from the Army. He did all kinds of things and then got a job in the Orient Tea Warehouse".

As communities across Britain rebuilt in the early 1950s, the Orwells joined the Bethnal Green Labour Party and began campaigning. John Orwell was elected as a local councillor and in 1966 and in 1971 served as Mayor of Tower Hamlets, making Beatty the Mayoress.

She said : "Our council was the best council, they were best to the old people. We used to go and visit all the old people’s homes. I never told them I was coming because I used to try and catch them out. We checked the quality of food and how clean it was. I was a councillor for ten years from 1972 until 1982. I had to fight to get the seat, but I always loved old people, my husband was the same. He was known as the ‘Singing Mayor’ because he used to sing in all the old people’s homes" As a measure of the substance of Beatty, she had started to visit old people in their homes on a friday night and fifty-nine years later, in 2018, when she was one hundred and one, she was still doing it : "From when I was forty-two, I used to go round old people’s homes on Friday nights and I still do it. We have dinners together, turkey, roast potatoes and sausages, with trifle for afters".

When interviewed by Louise Raw for the 'Morning Star', when Beatty was asked : when passing British Fascists on the streets of the East End of London, was it frightening for her, as a young Jewish girl, then of only about 15 or 16, to have to walk past them? Beatty replied :

Well – I shouted at them. "Fascist bastards. I’m afraid ! "

When Louise asked Beatty what she would she say to those argue we shouldn’t get involved in spontaneously confronting far right groups in Britain today, she replied :

“You have got to try to stop them marching. You have to protest, whenever they appear. You can try not to get involved with fascists all you like – but if you don’t, they will get involved with you”.

* * * * * * * *

This post was composed with grateful thanks to Rachel Lichtenstein and 'Writers Mosaic'

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

Quite excellent, and yet the fascists remain across British society 😞

ReplyDelete