He was born Paul Hudson Douglas Findlay in Dunedin, New Zealand during the Second World War in 1943. the son of John Niemeyer Findlay, who was born in Pretoria, South Africa and Aileen, a New Zealander. His parents had met and married in 1941, while John was serving as Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy at Dunedin University, New Zealand. At the end of the Second World War. in 1945. Paul was moved with the family to South Africa for three years, where his father took up a post at the University of Natal at Pietermaritzburg.

In 1948, when Paul was five, he came to Britain as a result of his father becoming Professor of Philosophy at what was Kings College and later became the University of Newcastle upon Tyne. Mary Warnock, the philosopher, later referred to him as a 'noted Hegelian scholar and notoriously bad-tempered man.'

From the age of 11 he attended the prestigious independent school for boys, University College School, London with its magnificent hall and in 1961 gained a place at his Father's old Oxford College, Baliol, to study Greats. He followed this, after graduation in 1964, with study at the London Opera Centre. In the next two years he had a succession of appointments : He got his first job, at the age of 24, as 'Production and Technical Man' New Opera Company, followed by a brief spell as 'Director of London, Sinfonietta' in the same year. In 1968 he became 'Stage Manager' of Glyndebourne Touring Opera and English Opera Group and then in the same year moved to the Royal Opera House, Convent Garden as Assistant Press Officer, a position he held for the next four years.

At the age of 29 in 1972, Paul moved to work for senior management as 'Personal Assistant to General Director', John Tooley, a position he held for four years until his own appointment as 'Assistant Director of Opera'. Finally, he took over the mantle of 'Director' at the age of 44 in 1987. It was during his six year tenure that he did his ground breaking work to make opera and ballet accessible to new audiences and, as he said, ‘as wide a public as possible.’

Paul, seen here at the age of 37 in 1980, confessed that he would "sit gobsmacked" at board meetings as great minds like Noel Annan and Sir Isaiah Berlin debated the 'Ethics of running an opera house.' More importantly, he discovered Valery Gergiev when he was unknown outside Leningrad and did much to support artists in their early struggles. Norman Lebrecht in the Independent said : 'He was forever seeking to expand the audience base. Unlike most opera chiefs, he had no ego whatsoever.' With this in mind, he played a leading role in creating 'Schools’ Matinees', the first of which, in 1978, was sponsored to the tune of £20,000 by the Royal Opera House Trust and Friends on Convent Garden. In 1980 he got IBM to cough up £30,000 and J, Sainsbury £53,000 the following year. By this time six Matinees were being held each year, three opera and three ballet with about twenty presented in the regions by the Sadler's Wells Royal Ballet Company. His programme of matinees was backed up a scheme for low price performances for school parties. By the mid 1980s about 38,000 from 2,500 schools were attending each season.

Paul, seen here at the age of 37 in 1980, confessed that he would "sit gobsmacked" at board meetings as great minds like Noel Annan and Sir Isaiah Berlin debated the 'Ethics of running an opera house.' More importantly, he discovered Valery Gergiev when he was unknown outside Leningrad and did much to support artists in their early struggles. Norman Lebrecht in the Independent said : 'He was forever seeking to expand the audience base. Unlike most opera chiefs, he had no ego whatsoever.' With this in mind, he played a leading role in creating 'Schools’ Matinees', the first of which, in 1978, was sponsored to the tune of £20,000 by the Royal Opera House Trust and Friends on Convent Garden. In 1980 he got IBM to cough up £30,000 and J, Sainsbury £53,000 the following year. By this time six Matinees were being held each year, three opera and three ballet with about twenty presented in the regions by the Sadler's Wells Royal Ballet Company. His programme of matinees was backed up a scheme for low price performances for school parties. By the mid 1980s about 38,000 from 2,500 schools were attending each season.He also initiated 'Big Top Performances' for The Royal Ballet and Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, where the ballet companies performed in circus tents around the country and thus reached parts of the country it had never reached before.

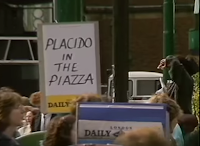

In 1987 he masterminded the first 'BP Big Screen' in Covent Garden Piazza and said at the time : "When it became known that we were going to give free performances of Boheme with Domingo, it's not a work that he's appeared in here for some time, and we knew there would be tremendous pressure on tickets and therefore we were very, very concerned to find a way to make these performances more available to the public."

Placido Domingo described the event as : 'such a wonderful and moving experience.'

In addition to the 750 promenaders in the stalls and 1300 more in the circle and gods inside the Theatre, thousands, outside in the Piazza, watched the performance relayed from five tv cameras on the big screen and listened for free, Paul had seen to it that the £45,000 cost was met by sponsors.

Paul also pioneered open-air opera concert performances at Kenwood House, Hampstead Heath, in addition to broadcasts of opera and ballet on BBC TV and radio. Further initiatives included, in 1991–2, The Royal Opera’s performances of 'Turandot' at Wembley Arena, seen by more than 50,000 people.

It was Paul who introduced the use of surtitles at the Royal Opera House, transforming audience response to opera performed in its original language by increasing its accessibility. Long after Paul was gone, Judith Palmer, surtitler in 2011 explained her role : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sdHgFiYPSo

It was Paul who introduced the use of surtitles at the Royal Opera House, transforming audience response to opera performed in its original language by increasing its accessibility. Long after Paul was gone, Judith Palmer, surtitler in 2011 explained her role : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sdHgFiYPSo

It was Paul who introduced the use of surtitles at the Royal Opera House, transforming audience response to opera performed in its original language by increasing its accessibility. Long after Paul was gone, Judith Palmer, surtitler in 2011 explained her role : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sdHgFiYPSo

It was Paul who introduced the use of surtitles at the Royal Opera House, transforming audience response to opera performed in its original language by increasing its accessibility. Long after Paul was gone, Judith Palmer, surtitler in 2011 explained her role : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sdHgFiYPSoBetween 1976 and 1988 he arranged more than 50 tours of the Royal Opera House companies to more than 30 countries, including China, India, Korea, the Soviet Union and New Zealand. At the same time he was responsible for bringing many visiting companies to the Royal Opera House, including La Scala, Milan, New York City Ballet, Paris Opera Ballet, Bolshoi Ballet, Kirov Opera and Ballet, Dance Theatre of Harlem and Central Ballet of China. He also strengthened links with other British companies through co-productions and shared performances, particularly with Scottish Opera and Welsh National Opera.

As Director he was responsible for the British premier of Berio’s 'Un re in ascolto' in an award-winning production by Graham Vick and world premiere of Harrison Birtwistle’s 'Gawain', broadcast on BBC TV and Götz Friedrich’s 'Ring Cycle', conducted by Haitink. In 1988 he saw to it that Sian Edwards became the first woman to conduct at Covent Garden, conducting performances of Tippett’s 'The Knot Garden.'

In relation to the end of his contract at the Royal Opera House, in the opinion of the philosopher Mary Warnock, who interviewed Paul for her book, 'Nature and Mortality', he told her he wanted to get out of, what he referred to as 'this place' and was looking for another job. 'I don't think Findlay's desire was generally well known. He was, in fact, eased out by Nicholas Payne, a far calmer character and better musician.' Paul put his own gloss on events when he referred to the new General Director, Jeremy Isaacs : 'My contract was coming up and he wanted to have his own men.'

Paul's next appointment was in 1993, when, at the age of 50 and for two years he became Managing Director Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. According to Anthony Everitt in the Independent, he 'took the biggest gamble of his life by joining the RPO. The slight change in his employer's initials marked a move from Britain's best-funded arts organisation to one that was apparently on the brink of extinction.'

As Everitt wrote of Paul in 1995 that he was : 'an enthusiast, always optimistic and always full of energy. He talks with extraordinary rapidity, words and ideas tumbling from his lips. He soon persuaded the RPO that the future lay in developing its work outside London, while maintaining a metropolitan presence. He quickly negotiated a residency in Nottingham, established a special relationship with the resurgent Royal Albert Hall and, in partnership with Raymond Gubbay, adopted some of the techniques of rock and pop concerts (laser lighting and the like): RPO performances became not just musical but theatrical events.'

In relation to his short tenure, Everitt described him as : 'a good guy with bad luck. The players of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra have just sacked him as their managing director. He does not deserve the blow that has struck him down.' He went on to say that Paul was 'essentially defeated by circumstances beyond his control. The RPO is not the first self-governing orchestra to resent the strong leadership that is today essential for success.'

In 1997 he became Planning Director of the European Opera Centre and then in the same year and for the last 14 years of his career, until his retirement at the age of 68 in 2011, the Director of the 'Arts Educational Schools', which was founded in 1919 and grew to provide specialist vocational training training in musical theatre and acting for film and tv.

In 1997 he became Planning Director of the European Opera Centre and then in the same year and for the last 14 years of his career, until his retirement at the age of 68 in 2011, the Director of the 'Arts Educational Schools', which was founded in 1919 and grew to provide specialist vocational training training in musical theatre and acting for film and tv.

Alex Beard, Chief Executive of the Royal Opera, said of Paul :

'His dedication and commitment to this great institution was coupled with a determination to extend the reach of both opera and ballet, ensuring that both new and wider audiences had the opportunity to enjoy these remarkable art forms.'

What better valediction might an old opera company director have ?