Page views : 1850

Peter, who has died at the age of 88 and whose career in electronic music ran, on and off, for almost 50 years, was born in London in 1933, the son of Sofka and Leo who had both left Russia after the Communist Revolution in 1917, when his mother was Princess Sofka Dolgorouky. She had arrived in Britain, with her grandmother, at the age of 12 in 1919, in a British warship, in a party led by the Dowager Empress who was met at Portsmouth by Queen Alexandra, the Empress's sister.

Peter, who has died at the age of 88 and whose career in electronic music ran, on and off, for almost 50 years, was born in London in 1933, the son of Sofka and Leo who had both left Russia after the Communist Revolution in 1917, when his mother was Princess Sofka Dolgorouky. She had arrived in Britain, with her grandmother, at the age of 12 in 1919, in a British warship, in a party led by the Dowager Empress who was met at Portsmouth by Queen Alexandra, the Empress's sister.

In comparison Peter's father, although related to the Kings of Serbia, arrived as a penniless émigré and subsequently built a successful career in Britain as a civil engineer. Leo amicably separated from Peter's mother when he was 4 years old in 1937 and when this photo was taken in 1939, his mother had married Grey Skipwith and Peter, on the left, and his brother Patrick, on the right, sit between their mother and new step brother, Ian.

In comparison Peter's father, although related to the Kings of Serbia, arrived as a penniless émigré and subsequently built a successful career in Britain as a civil engineer. Leo amicably separated from Peter's mother when he was 4 years old in 1937 and when this photo was taken in 1939, his mother had married Grey Skipwith and Peter, on the left, and his brother Patrick, on the right, sit between their mother and new step brother, Ian.  consisted of going to concerts occasionally, playing the piano and playing thundering duets with my grandmother and listening occasionally to classical radio, the Third Programme, which my grandfather would mark on the Radio Times and we would specifically stop talking when that programme was played. Then the conversation would start afterwards". In addition to music, Peter also had a youthful fascination with building DIY radio sets and recalled : “I can still smell the shellac. I was fearless about wiring – and about music”.

consisted of going to concerts occasionally, playing the piano and playing thundering duets with my grandmother and listening occasionally to classical radio, the Third Programme, which my grandfather would mark on the Radio Times and we would specifically stop talking when that programme was played. Then the conversation would start afterwards". In addition to music, Peter also had a youthful fascination with building DIY radio sets and recalled : “I can still smell the shellac. I was fearless about wiring – and about music”.  At the age of 11 in 1942, he joined Royal Grammar School for Boys in Guildford and recalled : "Occasionally at school there were communal choirs, otherwise there was no music". He was only at the school a few years before he was packed of to the boys public school, Gordonstoun in Scotland as a boarder. It was described some years later by another alumnus, Prince Charles, as “Colditz in kilts”.

At the age of 11 in 1942, he joined Royal Grammar School for Boys in Guildford and recalled : "Occasionally at school there were communal choirs, otherwise there was no music". He was only at the school a few years before he was packed of to the boys public school, Gordonstoun in Scotland as a boarder. It was described some years later by another alumnus, Prince Charles, as “Colditz in kilts”.

After graduating he continued his studies and gained his doctorate, a D.Phil in Geology at the age of 25 in 1958, having been supervised by the geologist, explorer and mountaineer, Lawrence Wager and having stayed in a bothy mapping dormant volcanoes in the Cuillin Mountain Ridge on the Isle of Skye in Scotland.

Now, employed as a geologist : "I had a job in Pakistan's St. George's, looking for water. (link) I then got married. Married a girl of 17 whose parents did not want their daughter to go to Antarctica or wherever it was the jobs were on offer". It was 1960 and the upper class girl in question was Victoria Heber-Percy. "So I decided to stay in London and became a mathematician at the Air Ministry which was a terrible, terrible Civil Service job". From working on atomic physics he said :"I thought I'd do something completely new and I started to do electronic music. So I bought a tape recorder and a few oscillators from junk shops in the East End of London and the hunt was on. I got bitten by the bug and at that time I was very, very innocent, really. I thought that this is a new subject. Nobody, nobody had heard about electronic music. Nobody knew about this. Only me. And so I continued in this lovely, idyllic really, notion, that whatever I did, I was alone in the world". A complete novice, Peter found that he "really didn’t even know how to cut up a tape. So somehow I found out about Daphne Oram (composer and electronic musician) and asked her to give me lessons, which she did. She gave me homework like making up a tune out of bits of spliced tape and things like that; speeding up and slowing down tape recorders". Supported financially by Victoria, Peter recalled he "built up this amazing cacophony of gigantic instruments without any clear notion as to which direction I should take". Between 1966–67, Peter worked in the shed with

A complete novice, Peter found that he "really didn’t even know how to cut up a tape. So somehow I found out about Daphne Oram (composer and electronic musician) and asked her to give me lessons, which she did. She gave me homework like making up a tune out of bits of spliced tape and things like that; speeding up and slowing down tape recorders". Supported financially by Victoria, Peter recalled he "built up this amazing cacophony of gigantic instruments without any clear notion as to which direction I should take". Between 1966–67, Peter worked in the shed with  Delia Derbyshire, from the BBC TV Radiophonic Workshop, who had created BBC TVs 'Doctor Who' main theme in 1963 (link) and Brian Hodgson, the series Sound Effects Creator. Together they ran 'Unit Delta Plus', an organisation to create and promote electronic music and ran a concert of electronic music at the Watermill Theatre in 1966.

Delia Derbyshire, from the BBC TV Radiophonic Workshop, who had created BBC TVs 'Doctor Who' main theme in 1963 (link) and Brian Hodgson, the series Sound Effects Creator. Together they ran 'Unit Delta Plus', an organisation to create and promote electronic music and ran a concert of electronic music at the Watermill Theatre in 1966.

Paul McCartney recalled visiting Peter and Delia in “a hut at the bottom of the garden full of tape machines and funny instruments”. This led to a 1967 collaboration at the Roundhouse in London billed as a 'Million Volt Light and Sound Rave' with 'music by Paul McCartney and Unit Delta Plus'. The works performed included McCartney’s 14-minute avant garde electronic composition 'Carnival Of Light', which the Beatles recorded, but which has never been released. Peter once said : “I’d like to get in touch with him about it, but I’m quite in awe – how do you get in touch with God?”

Paul McCartney recalled visiting Peter and Delia in “a hut at the bottom of the garden full of tape machines and funny instruments”. This led to a 1967 collaboration at the Roundhouse in London billed as a 'Million Volt Light and Sound Rave' with 'music by Paul McCartney and Unit Delta Plus'. The works performed included McCartney’s 14-minute avant garde electronic composition 'Carnival Of Light', which the Beatles recorded, but which has never been released. Peter once said : “I’d like to get in touch with him about it, but I’m quite in awe – how do you get in touch with God?”

It wasn't long before differences emerged between Peter and his partners : "The idea was that we would make a fortune doing commercial sounds, but I wasn’t interested in doing commercial sounds. We did one for Philips, which was something like “Whoooop”, and that was it. We got a lot of money for that, but I didn’t want to do that, so we split. But they didn’t succeed either. I didn’t want to have a commercial studio, I wanted an experimental studio, where good composers could work and not pay. In fact, rather like this organization, the same sort of philosophy. If anyone had a good project, they could come and work in my studio and I wouldn’t charge them'.

In 1968 Peter's existence was publicised when he featured in an episode of BBC Television's 'Tomorrow's World' (link) with the narrator explaining : "On the river near Putney Bridge there's a computer at the bottom of the garden. This is the workshop of a composer, Peter Zinovieff, where you no longer have to twiddle the knobs and produce electronic music; a computer does it for you and it can produce random scales, drumbeats or even perform a quartet".

In 1968 Peter's existence was publicised when he featured in an episode of BBC Television's 'Tomorrow's World' (link) with the narrator explaining : "On the river near Putney Bridge there's a computer at the bottom of the garden. This is the workshop of a composer, Peter Zinovieff, where you no longer have to twiddle the knobs and produce electronic music; a computer does it for you and it can produce random scales, drumbeats or even perform a quartet".  Although he admitted that his garden shed set up was “incredibly cumbersome and primitive”, it enabled him to compose such works as 'Partita for Unattended Computer', which he organised with Tristram and performed at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1968. (link) It was, he claimed, “the first real-time performance on stage of any electronic music not using tape”.

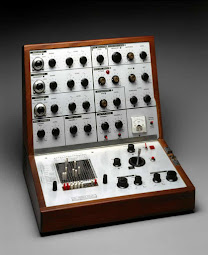

Although he admitted that his garden shed set up was “incredibly cumbersome and primitive”, it enabled him to compose such works as 'Partita for Unattended Computer', which he organised with Tristram and performed at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1968. (link) It was, he claimed, “the first real-time performance on stage of any electronic music not using tape”. At the age of 36, Peter started, what were to be, the most important collaborations in his life when he started working with Tristram Cary and David in his newly formed company, 'Electronic Music Studios' with its slogan : 'Think of a sound - Now make it'. In the years that followed they pursued ground-breaking creativity, designing portable and elegant synthesisers including their bestselling VCS3. Peter recalled that in his working relationship with David : "I would say some mad idea : "Can we have this ?""I want this" (link) and he would produce it. He would understand exactly what my pathetic way of putting something was. He would be able to interpret it into a concrete electrical idea and make the bloody thing and it worked". He recognised David as the "the real, real genius in electronic music device making".

By this time Peter had moved the studio from the shed into the house "It was very luxurious in the end. (link) It occupied the bottom of the house and then we bought the house next door, so it was two houses and one half of the basement was the studio and the other was a wonderful listening room. It was like a little theatre with a range of carpet seats and I could control everything in the studio, it was sound-proofed from there".

By this time Peter had moved the studio from the shed into the house "It was very luxurious in the end. (link) It occupied the bottom of the house and then we bought the house next door, so it was two houses and one half of the basement was the studio and the other was a wonderful listening room. It was like a little theatre with a range of carpet seats and I could control everything in the studio, it was sound-proofed from there".![]() When it came to the VCS3, Peter recalled : “I had a nice time teaching Ringo Starr how to use it. I would go to his house in Hampstead. He wasn’t particularly good. But then neither was I”.

When it came to the VCS3, Peter recalled : “I had a nice time teaching Ringo Starr how to use it. I would go to his house in Hampstead. He wasn’t particularly good. But then neither was I”.

Peter's synthesiser was used by Pink Floyd on the track 'On the Run' (link) on their 1973 album, 'Dark Side of the Moon'. In 1977 Brian Eno used it on the atmospheric flourishes on David Bowie's 'Heroes'. (link)

Peter's synthesiser was used by Pink Floyd on the track 'On the Run' (link) on their 1973 album, 'Dark Side of the Moon'. In 1977 Brian Eno used it on the atmospheric flourishes on David Bowie's 'Heroes'. (link)  Another 'god-like' visitor to the studio was Karlheinz Stockhausen who visited the studio Peter described as : “He was very brusque and German. I didn’t find him very sympathetic. It was as if he knew everything, but he didn’t know anything about my equipment.” Nevertheless, he still used one of Peter's later synthesizers, the Synthi 100, on his 1977 electronic composition 'Sirius'. (link)

Another 'god-like' visitor to the studio was Karlheinz Stockhausen who visited the studio Peter described as : “He was very brusque and German. I didn’t find him very sympathetic. It was as if he knew everything, but he didn’t know anything about my equipment.” Nevertheless, he still used one of Peter's later synthesizers, the Synthi 100, on his 1977 electronic composition 'Sirius'. (link) Although Peter supplied his synthesizers to rock bands, he preferred his collaboration and friendship with Harrison Birtwistle and Hans Werner Henze and said : "That side of music could be called classical electronic music, or serious electronic music rather than pop". He wrote the libretto for Harrison's opera, 'The Mask of Orpheus' during the 1970s.

Although Peter supplied his synthesizers to rock bands, he preferred his collaboration and friendship with Harrison Birtwistle and Hans Werner Henze and said : "That side of music could be called classical electronic music, or serious electronic music rather than pop". He wrote the libretto for Harrison's opera, 'The Mask of Orpheus' during the 1970s. Peter's studio workshop was passed to the National Theatre for 'safe keeping' and placed in storage in a basement. When he paid it a visit it pained him to say : "It had been chopped to pieces with wire cutters and saws and there was a leak and rain was pouring on it. It was heart-rending". (link)

Peter's studio workshop was passed to the National Theatre for 'safe keeping' and placed in storage in a basement. When he paid it a visit it pained him to say : "It had been chopped to pieces with wire cutters and saws and there was a leak and rain was pouring on it. It was heart-rending". (link)

Peter now moved to Raasay, an island off Skye, where he had built a home from the ruins of an old crofter’s cottage. Harrison also bought a property on the island, where one of Peter's last remaining synths was reputedly powered by a windmill in what Peter called “the dying echo of my work”.

Peter now moved to Raasay, an island off Skye, where he had built a home from the ruins of an old crofter’s cottage. Harrison also bought a property on the island, where one of Peter's last remaining synths was reputedly powered by a windmill in what Peter called “the dying echo of my work”.

In 2012 when Matthew Ritchie's sonic temple, 'The Morning Line', made from 20 tons of black coated aluminum was to be moved to its permanent installation in Karlsruhe in Germany, Peter was commissioned to provide the audio composition to be delivered via 40 Meyer speakers controlled by an advanced multispatial audio system designed by Tony Myatt from the Music Research Centre, University of York. Peter provided 'Good Morning Ludwig'. He said : “I went to Beethoven and asked him : "Good morning Ludwig, I want to do some variations on your work – what would you like me to do?" So we had this conversation”.He also worked with the poet Katrina Porteous on her poem 'Sun' (link) in 2016 and Peter based his composition for her 'Under the Ice' (link) on recording taken of sounds made by Antarctic glaciers. The 30 min performance was broadcast online on the 23rd June - the day Peter died.

Looking into the future in 2018, at the age of 85, Peter said : "I would like to have much more human communication with whatever it is that makes electronic music, even though its electronic music and not instrumental music. There's a huge way to go and even then, it will only be the beginning". Two years later he was thrilled to have been given a state-of-the-art Syntryx synthesiser and enthused that : "It's really a marvellous bit of kit (link) and it reminds me so much of 50 years ago when I got my first VCS3".

Peter's daughter, Sofka said : 'Amongst Peter's very last creations - this year - was a collaboration with his granddaughter, my musician daughter, Anna Papadimitriou. It’s a terrifying piece about Covid called Red Painted Ambulance. Peter uploaded it to his website just before the fall that led to his death - an indication of how much he was still working and thinking about ambitious music'. Anna plays in the band, HAWXX.“My wonderful head full of wild things bursting out and having to be tamed. Lots of people would say, "Oh, this is too daring". But I’ve never felt that. Perhaps because I’m Russian, I’m not afraid of going too far”.

No comments:

Post a Comment