.jpg) Page views : 585

Page views : 585

Mike who died on the 5th April at the age of 101 and was in active service during the Second World War for five years and received an obituary in the 'Times' and 'Telegraph' and a notice of his passing in the 'Wirral Globe', but no other press coverage and only a eight mentions on Twitter. On the other hand the passing of another old Second World War veteran, Harry Billinge, who died on the 5th April at the age of 96 and was in active service for two years in the War, received widespread press, TV and radio coverage and comment in social media. This can partly be explained that Harry's face was familiar because he spent more than 60 years collecting money for the Royal British Legion. He also helped raise more than £50,000 for the British Normandy Memorial and would visit the site in Northern France each year and it was his appearance on BBC Breakfast TV in 2019 which saw him go viral.(link) By contrast, Mike's part in the conflict would have remained unknown, had it not been for the publication of Gavin Martin's book, 'The Men Who Made the SAS', published in 2015.

* * * * * * *

.jpg)

Mike was born 'Stuart Michael Carr' in the Autumn of 1920 in the town of Frome in Somerset and later moved with his elder brother and two sisters, 140 miles north, to the market town of Stone in Staffordshire where his father, an accountant, became manager of the Joules Brewery. Before this his father and grandfather had both belonged to a family of Anglo-Irish soldiers. Mike must have been an adolescent when they moved, witness the facts that : it was in the West Country that he had learned to use a shotgun and he never lost his Somerset accent. He was already something of a dare-devil who could remember the times he trespassed on railway lines and watched the express trains go by so close, he could have almost touched them.

Mike was born 'Stuart Michael Carr' in the Autumn of 1920 in the town of Frome in Somerset and later moved with his elder brother and two sisters, 140 miles north, to the market town of Stone in Staffordshire where his father, an accountant, became manager of the Joules Brewery. Before this his father and grandfather had both belonged to a family of Anglo-Irish soldiers. Mike must have been an adolescent when they moved, witness the facts that : it was in the West Country that he had learned to use a shotgun and he never lost his Somerset accent. He was already something of a dare-devil who could remember the times he trespassed on railway lines and watched the express trains go by so close, he could have almost touched them.

His mother was ambitious for her two sons and both gained a place at Alleyne’s Grammar School for Boys in Stone, with its Tudor origins and motto : 'Nisi Dominus Frustra / Without the Lord everything is in vain'. Although Mike was not an academic enthusiast, he was encouraged by his grandfather, who worked on the passenger ships to Australia, to take an interest in astronomy and navigation. With his help, he made a theodolite, using pieces form his Meccano set for boys and used it as a navigation surveying instrument with a rotating telescope for measuring horizontal and vertical angles.

.jpg)

Meanwhile, to the west, in North Africa, Italy, which had declared war in June 1940 and a huge army in Libya which threatened the Suez Canal in British-occupied Egypt which was critical to Britain's communication with India. The Libyan Desert posed a challenge to both sides with its vast sand dunes making it all but impossible for large forces to penetrate inland. It was now that Major Ralph Bagnold of the Royal Signals, who had spent much of the 1920s and 1930s exploring the desert suggested to General Sir Archibald Wavell, 'Commander-in-Chief Middle East', that he formed a desert scouting force, a small body of motor commandos, never more than 350 strong, known as the 'Long Range Desert Group'. Wavell readily agreed, and the LRDG began operations in September. There was no shortage of volunteers, but what Bagnold wanted first and foremost, were navigators. When he told this to Brigadier John Chrystall, Commander of the Yeomanry Cavalry Brigade in Palestine, whom he met by chance in Cairo, the Brigadier said he had just the man, namely a 'Trooper Carr', who had just guided him through the buffer zone between Syria and Palestine. Given the lesson he learned from his grandfather Mike said : “I took to navigating easily. I’d trained as a surveyor and was comfortable using a theodolite”.

When Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon Cox-Cox of the Staffordshire Yeomanry, who had taken a dislike to Mike, who stood head and shoulders above the rest of the Regiment, both in size and intellect, refused to to give him a 'leg-up' and release Mike, the Brigadier sent sent two military policemen with instructions to escort Mike to the LRDG’s base in Cairo. There he joined 30 other 'possibles' from the cavalry division and was one of eight accepted to join. After a brief interview by Lieutenant-Colonel Guy Prendergast said to Mike : "You're ready-made".(link)

They were told by Captain Pat McCraith that they were : "Bagnold's blue-eyed boys" and they should "forget everything we had learnt up to now because we were no longer regular army". Mike said that he also : "Went on to give us a document which we signed and returned. It was our oath that we would never, for the whole of our lives, reveal what we had been up to in the LRDG".(link)

Mike, seen here on the left, wearing his woolen cap comforter, had a position in the LRDG which was important beyond his rank of 'lance corporal'. The Group prized Morse signalers and vehicle mechanics and, as in the navy, 'navigation' preceded 'gunnery' in importance. He soon made his presence felt since there were few men bigger than Mike in the Group. At six foot four inches, and nick- named 'Lofty', he weighed fifteen stone, had the brawn of a rugby player and the brains and ability of a top rank navigator capable of finding his way in the flat, featureless and unforgiving expanse of expanse of the Libyan Desert. Using his natural strength, the heavy Vickers K machine gun was his weapon of choice. It was a frightening gas-operated weapon that fired 1200 rounds per minute and Mike had a handle fitted and used his strength tp fire it from the hip.

For navigation in the desert by day, Bagnold had invented a 'sun compass', which was a reliable, but rough indicator which was of no use by night. The theodolite, with its astral fixes, reduced the chance of error dramatically and Mike said that, in terms of accuracy : “In the desert I was down to 200m". Later in the War, during a discussion on whether navigation was an 'art' or a 'science', he amused Major Bagnold by suggesting it was : "The art of getting lost scientifically". Mike remembered one particular they had about the word 'courage'. He said : "One of the things I speculated with Bagnold about was whether people started with a reservoir of courage" and then it went down and was extinguished or increased with more action and experience. He ended with : "Bagnold never offered a solution, he offered examples that made me think".

Mike also found himself teaching navigation to the Special Air Service, formed by Colonel David Stirling in 1941, for offensive action behind enemy lines after the Germans had joined the Italians in North Africa that year. Indeed, Stirling tried to poach him, but Mike said “No” on the grounds that the SAS’s selection of recruits was too slack. He later said :"The LRDG was a group in which every single man was a specialist in something, while people will tell you, not least people connected to the SAS, that the SAS absolutely worship the LRDG”. “We were regarded as an undisciplined rabble - but we were not a bunch of thugs. We were composed of selected people who all had a particular skill that was needed at that time. We had one specialist in knocking people about, because sometimes that had to be done, but most of us just did our own jobs. To serve in the unit was a privilege. The camaraderie was magnificent, it was a family”.

The LRDG, the secretive unit, which : never numbered more than 350 men; went deep behind enemy lines; stayed hidden for days in ditches or bushes just yards from the enemy; were unable to light fires in the freezing desert nights; rationed their water so tightly they were taught to “wash” using sand. As to his role, Mike said : “Being a navigator was extremely challenging. One minor fault or miscalculation could have tragic consequences, but I have no regrets whatsoever”. As a matter of interest, the men only wore the Arab headdress for the camera and preferred their cap comforters the the desert.

The LRDG, the secretive unit, which : never numbered more than 350 men; went deep behind enemy lines; stayed hidden for days in ditches or bushes just yards from the enemy; were unable to light fires in the freezing desert nights; rationed their water so tightly they were taught to “wash” using sand. As to his role, Mike said : “Being a navigator was extremely challenging. One minor fault or miscalculation could have tragic consequences, but I have no regrets whatsoever”. As a matter of interest, the men only wore the Arab headdress for the camera and preferred their cap comforters the the desert.

Out on patrol in May 1941, Mike recalled : "It was a terrible heatwave, even by desert standards. We ran out of water and just had to sit there. We even drank the radiator water. We were really absolutely done". When they got on the move he said : "The navigation was difficult because I was delirious". By force of will, he kept navigating until he saw the dome of the oasis town of Jaghbub in the distance. He must have passed out, because he said that when he woke up he was in the lap of the Patrols Medical Officer, Sandle who was bathing his lips with salt water. He said : "He was telling me : "I have a beautiful sister in Bristol and after the War, I'm going to introduce you". He never did".

In November his patrol, in their unmarked vehicles, came under attack from three low flying RAF Beaufighters and under cannon fire he was forced to run for his life and his truck caught fire. The following day the patrol was spotted but not attacked by two German fighters who he said : "Waggled their wings waved to us and cleared off".

Early in December his patrol spotted a large Italian camp at a road junction and he moved forward with the small bespectacled, Captain Frank Simms. Mike recalled : "He was a hero of mine, one of the few men I have met who appeared to have no fear, or certainly ne was able to control his fear". He also "frightened the pants" off Mike because : "He just loved bumping people off. It's part of war, but he didn't feel the need to kill because there was a war. He just quite liked the idea". Mike was also intrigued by his gentler side, admiring wild flowers in a wadi of weeping over a bird dying in the heat. In the attack of the camp. Mike was separated from the patrol, which had assumed he had been captured. Mike returned to the wrecked enemy transport and when an Italian soldier leapt from the back of a truck and Mike, unsure if he was about to be attacked, instinctively fired his rifle and killed the man in mid air.

The Senussi were a Muslim political-religious tribe of desert nomads who had been brutally repressed by the Italians for years and in December 1941 he had much to thank them for. He was somewhere between Mekili and Berna in Libya when he became separated from fellow soldiers after raid which damaged 15 enemy vehicles and decided to walk to rejoin his unit. He now ended up seeking refuge in a Senussi camp, where he hid from patrolling Germans by dressing as an Arab. He remained a guest of the Senussi for more than a week and said : “I was provided with camel’s milk, macaroni and coffee by the natives”. He also became ill as a result of drinking down the camel dung the Senussi had drooped in the milk for medicinal reasons. He was now moved to a bed in the Sheikh's smaller tent and over a period of days, recovered and went to the water in a ravine, a 'wadi' where he scalded himself : "To kill bugs. fleas, etc".

During his time with them, he recalled saving the life of an Australian airman who had crashed in the desert, 40 miles from the camp. He recalled : “I dressed him as an Arab and put him on a donkey and we easily got through the German lines. He would have died within two days if I hadn’t got to him – but years later I read a book about how this airman found a donkey and was returned to safety, but it didn’t mention me!”

Still separated form his unit and lying beneath a heap of camel saddles in the camp, Mike watched as six tanks rumbled towards him. The drivers’ cap badges looked familiar and he hoped to cadge a lift back to his own unit with what he thought was a British convoy. However, as he broke cover and walked towards the armoured vehicles, he realised his mistake. They were German tanks, part of Rommel’s fearsome Afrika Korps and he was in their line of fire. He said : “The roundels on their forage caps looked like the RAF’s and I remember thinking ‘I didn’t know the British had those’. Fortunately, I was dressed as an Arab, so I very quietly turned around and ducked into a tent”. When he finally made it back to base, two days before Christmas in 1941, his native disguise was so convincing officers suspected he was a spy.  Cecil Beaton,

Cecil Beaton, operating as a war photographer was sent by the Ministry of Information to Cairo in 1942 to photograph celebrities of the desert war, including the LRDG. He was also amused to photograph the “idlers” in the Group who spent their time at Shepheard’s Hotel, whom he dubbed the SRSG : 'The Short Range Shepheard’s Group'. In addition, to photos of the Group he also caught this striking image of Mike in which he captured the young and determined warrior.

In September 1942, Mike was a member of the force whose target was the Italian fort at Jalo, a desert oasis some 250 miles south of Benghazi on the Libyan coast, 500 miles beyond the allied lines. As a prelude to General Montgomery’s coming offensive at El Alamein, the LRDG, supported by Sudanese troops led by British officers, were ordered to capture Jalo.

Their long approach through the Libyan desert had gone well. Mike always said that after the first 50 miles, the only real danger was from aircraft, and not just the enemy’s. Their final approach was on foot in pitch darkness, carefully skirting a minefield, with Mike at the head of the leading column. All went well until promised success until a sentry shouted a challenge in Italian and Mike silenced him with a burst from his Vickers and the fort erupted with small-arms and mortar fire. The Sudanese soldiers who accompanied the Group fled and a mortar round incapacitated the LRDG commander. Unexpectedly the Germans had reinforced the post.

Mike, whose Vickers had a rate of fire of more than a thousand rounds a minute, covered the withdrawal until his gun abruptly stopped. The copper firing caps in the base of the .303 cartridges had melted, and jammed the mechanism. There was nothing he could do to clear the stoppage and there were Italian voices approaching. He now edged back round the minefield, but could find no one from the patrol. Eventually stumbling into the low wall of a well, climbed over, crouched low and waited. He slipped away before dawn and hid in a henhouse, but was captured flown to Benghazi for interrogation and, as a prisoner of war, was put on a ship to Taranto, in Southern Italy.

Mike said : “The Americans took me on trust. This big Yank gave me a tin of soup and the moment I smelled the soup I thought of my mother’s kitchen. I started crying and the big Yank took me on his knee and he started crying. When we had finished, I think everyone there was crying!” He had been travelling for two months and weighed just seven stone and was now flown back to Britain. After a few days’ leave he rejoined the LRDG, who were training in Scotland for redeployment to the Far East, but this came to a sudden halt when the Japanese surrendered in August.

During the course of the War, Mike had been reported to his parents as 'killed in action'. He said : “My mother later told me how my father would approach her with the telegram in his hands. I then turned this round in my mind, and I thought if I shot some poor German, then somewhere in Germany someone was going to be told the same thing.” He said : “I just wish it had never happened, but being part of a secret unit and because of the type of work I was involved with, it happened three times to my poor mother and father. My parents were told I was missing, believed killed in action".

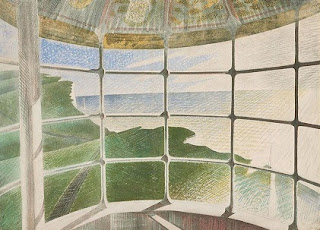

The LRDG, was disbanded at the end of the war and Field Marshal Montgomery himself said : "Without them, after El Alamein we would have been launching ourselves into the dark". Mike returned to the Atlas Insurance Company, becoming a building surveyor and valuer for their Liverpool office, and living on the Wirral for the rest of his life. In his mid-forties, when Atlas joined a larger group, Mike decided on a career change. An accomplished artist, particularly of birds and wildflowers, as well as a woodcarver and potter, he read for a degree, gained a teaching certificate and taught art until retirement.

Military historian, Gavin Mortimer, who made a number of references to Mike in his book 'The Long Range Desert Group' said : “Lofty Carr is one of the very last of the Greatest Generation, and during the Second World War he was one of the very greatest". Given the number of men Mike had killed in combat he was understandably equivocal about his role in the War and said : “I am not proud of anything" and “I am thoroughly ashamed of the War and everything to do with it. I can’t believe people behaved like that".

Modest and self-effacing, Mike himself said :

“I’m not special, everyone would always tell me that I am, but no, I am not special. I’m just one of the many people and soldiers who went out. I was lucky, I had four million other soldiers helping me and most of them were engaged in far more dangerous work.”

In grateful acknowledgement to Gavin Martin and his book : 'The Men Who Made the SAS',

Dr James Derounian, was a National Teaching Fellow and Visiting Professor at the University of Bolton. He specialised in research and teaching around community engagement, rural issues, and blended learning who retired at 62, was forced to return to work at 62. He was not alone when he said :

Dr James Derounian, was a National Teaching Fellow and Visiting Professor at the University of Bolton. He specialised in research and teaching around community engagement, rural issues, and blended learning who retired at 62, was forced to return to work at 62. He was not alone when he said : .jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)